RACHEL LACHOWICZ Review / Artillery Magazine Jan/Feb 2011

News

RACHEL LACHOWICZ Review / Art Ltd. Jan/Feb 2011

BRAD SPENCE “(figs.)”

January 8 - February 12, 2011

Opening Reception: Saturday, January 8 / 5:00 - 7:00 pm

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to open the 2011-year with a solo show of new paintings by Brad Spence.

The exhibition titled (figs.) features a series of new paintings reminiscent of a cinematic “dream sequence.” This exhibition is the culmination of the artist’s decade long exploration of the field of psychology, and the various institutions that attempt to rationally frame the human psyche.

The hazy, soft-focus paintings evoke a journey into the murky regions of the unconscious. Created with an airbrush, the works present themselves as illustrations, or evidence, as suggested by the title (figs.), for an unnamed text or crime, which eludes the viewer.

In a procession of disconnected images, with settings that shift from the domestic to the institutional, and symbols that appear pregnant with meaning, the feeling of disorientation gives way to a sense of terminal logic.

In grappling with the ultimate uncertain terrain of the unconscious, the artist draws upon a spectrum of references that include textbook Freudian psychoanalysis, clinical psychology, and Hollywood film, as well as healthy doses of personal confession.

Brad Spence has exhibited extensively in Los Angeles including an exhibition at The University Art Museum in Long Beach, CA; as well as exhibited world wide in Norway, Istanbul, Turkey, New York, NY, Paris, France and Germany. This exhibition is accompanied by a 60-page catalogue with essay by Erik Frydenborg.

For more information please contact Marichris Ty at marichris@shoshanawayne.comARLENE SHECHET / Jerry Saltz's Top 10 Art Shows of 2010

9. Arlene Shechet, “The Sound of It”

Jack Shainman Gallery

It’s exciting to see artists using materials that, until recently, were ridiculed by the art world for being decorative or crafty. And somehow Shechet turned a variety of gnarly, curling, enigmatic (and oddly sexy!) objects into a convincing language of sculptural form.

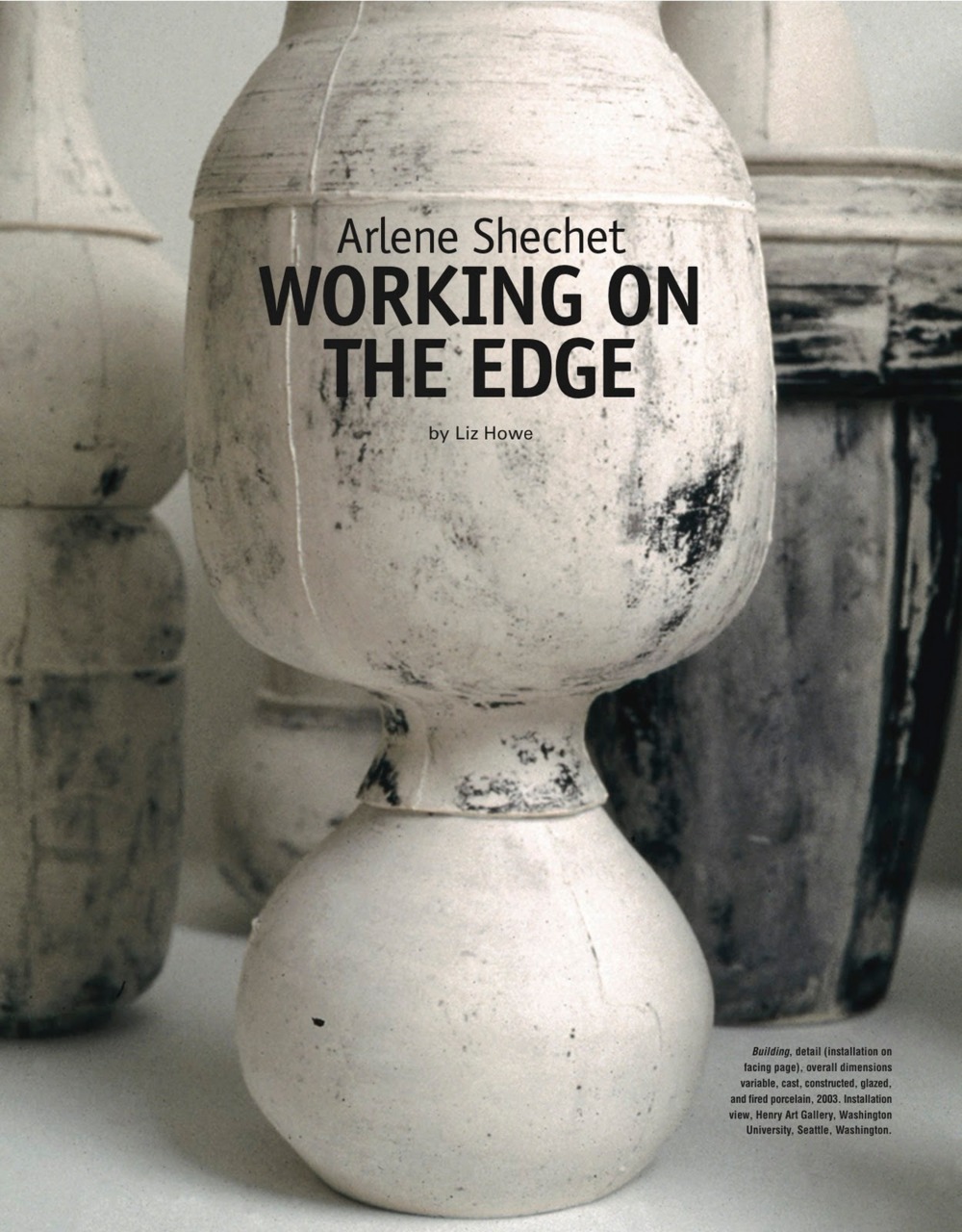

ARLENE SHECHET / Ceramics Monthly December 2010

CHIE FUEKI / ARTnews December 2010

The Great American (Male) Nude

Turning the tables on art-historical tradition, more women artists are depicting the naked male bodyby Lilly WeiIn thinking about women’s prospects in the arts over the past half century, I realize we’ve indeed come a long way from the stereotype of the active male artist and the passive female muse—men looking at women and women looking at themselves being looked at. Given women’s greater autonomy in general and in sexual matters in particular, it should be payback time, a chance for the woman artist’s gaze to linger on the naked male body as a source of esthetic delight and desire. Yet, “nude” remains virtually synonymous with the female body.

Instead of ratcheting up the male body count, female artists such as Lisa Yuskavage, Jenny Saville, Ghada Amer, Vanessa Beecroft, Marlene Dumas, and countless others have joined men in portraying women, whether themselves or others. Conversely, while recent decades have seen hard-core male sexuality and phalluses in greater evidence on gallery walls, more often than not these works are instances of men being depicted by other men, from Lucian Freud to David Hockney, Paul McCarthy, and Juergen Teller to, most notoriously, Robert Mapplethorpe.

So why are there so few stripped-down males, their charms unveiled by women for the delectation of women? While there is no one answer, some artists say that men’s bodies are less esthet ically pleasing; others suggest that women need to take back the female body, not colonize or promote those of men. Women—in fact most viewers—still have difficulty scrutinizing male genitalia, or, conversely, men resist being scrutinized by women as subjects. It might make them feel too vulnerable, and that raises a question: Does the mere fact of being depicted naked feminize the male body?

Yet even if their numbers remain small, more and more female artists are taking on the subject of the male body. In the years since feminist art began in the ’60s, and especially in the last decade, women have been exploring the possible meaning of a “female gaze,” with approaches that range from coy to ambiguous to explicitly sexual.

Looking at the work of younger women artists today, we find glimpses of naked body parts and even genitalia in Cecily Brown’s sexy abstractions, for example, but her imagery is more about hide-and-seek amid gorgeous brushwork than putting the male body center stage. And Elizabeth Peyton on occasion paints naked men, but her characteristically androgynous figures—whether unclothed or not—signal chaste longing more than carnal knowledge. Dana Schutz offers schematized, hardly erotic renditions of male beauté in Frank on a Rock (2002) and Presentation (2005), in which the subject is laid out as if for a dissection. A similar lack of sexual engagement affects Chie Fueki’s Super (2004), featuring a great, shimmering superhero caged in a transparent box with glitter obscuring the nudity.

Sexuality, and its connections to power and violence, comes to the fore in Kara Walker’s narrative silhouettes. Yet the dominance of the racial discourse overshadows the nakedness of white rapists and their black female victims, making it a lesser point. In Matterhorn (1995), Hilary Harkness, departing from her paintings of miniature militant women, depicts an enormous white cow with a strapped-on dildo mercilessly abusing a naked man. According to Harkness it’s a depiction of artist Mel Bochner, her former professor at Yale: the picture is every female student’s revenge fantasy. For all their diverse approaches and motivations, these works raise another question: Why does so much sublimation and unease surround these descriptions of the male body, once considered the ideal of beauty?

Ranking among the heavy hitters of earlier generations to tackle the male body, Alice Neel is notable for her unembarrassed presentation of the nude. She was praised for her unexpurgated, psychologically acute studies of friends, family, and acquaintances. Joe Gould (1933) presents a Greenwich Village eccentric sitting on a chair with legs spread and penis not only proudly on display, but in triplicate. Neel explained she gave him this “tier of penises” in tribute to his exaggerated virility. A later Neel nude, from 1972, portrays artist and critic John Perreault, awkwardly lolling on a bed, head propped up by his hand, fully exposed. His flaccid phallus, the focal point of the composition, is perhaps more unnerving.

Women artists have more directly tackled the art-historical notion of the male gaze, turning it on its head. Now in her mid-90s, Sylvia Sleigh has been undressing her male subjects for dec ades. The model in Philip Golub Reclining (1971) looks into a large mirror in which the artist at work is also reflected. It appears to be an amalgam of two Velázquez paintings: the Rokeby Venus, one of the most seductive nude female backs in the history of art, and his masterpiece Las Meninas, in which the artist is shown as he paints the scene before us. A more recent work, from 2006, portrays a nude young man sitting in an Eames chair clutching the armrests. The work, featured in P.S. 1’s “Greater New York” exhibition earlier this year, suggests a provocative interpretation of another Velázquez, his canny portrait of Pope Innocent X.

Working in a similar vein, Ellen Altfest is noted for her meticulously detailed, trompe l’oeil paintings of quirky subjects as well as her sly, subtly charged portraits of male nudes that parody the male gaze. Some she presents with eyes closed, arms behind their heads, legs apart, mimicking a classic female nude pose. Penis (2006), an anatomically correct, crisply drawn close-up of the body part, offers an upending of Gustave Courbet’s Origin of the World (1866), an unblinking look at the male phallus that is both real and theatrical, perversely clinical but with an undertone of heat, appealing to the voyeur—and exhibitionist—in all of us.

Other artists find more subtle ways to critique the objectifying gaze, to make pictures about sex that are not about power and subjugation. Joan Semmel is best known for her ongoing series of almost photorealistic nude self-portraits—a repossession of the female body from the male gaze and a meditation on time and its effects. But she has also depicted male nudes and, in the ’70s, created suites of paintings that show her lover and herself in various stages of sexual engagement. Because she didn’t want to objectify the male body in the way women’s bodies have been objectified, Semmel says, she chose to highlight situations in which pleasure was mutual, adding that “women are not as much aroused by the sight of the male body as they are by implications of touch, followed by sight.”

Among photographers, it seems evident that many women are simply not overtly fixated on the male body as a source of visual titillation. Diane Arbus’s photographs of the residents of a nudist colony include men, but their nakedness is incidental—vulnerability and marginality are the themes, rather than sexuality. And Nan Goldin’s naked men are part of a nervy, narcissistic autobiographical narrative of extreme urban bohemia. Sam Taylor-Wood’s photographs of naked men do qualify as male nudes, despite the hothouse glamour that envelops them, making them look less exposed. Katy Grannan, on the other hand, comes closer to naked than nude, sexuality being beside the point. In some of her color photos of men outdoors—including one shown with a full erection—Grannan reminds us that being naked in public is criminal.

Yet photography’s immediacy is also suited to work that is unequivocally about sex. “As a European who was raised in a Mediterranean culture, I’m quite comfortable with the human body,” says photographer Ariane Lopez-Huici, who divides her time between New York and Paris. “However, male nudity is still a difficult subject.” In 1992 she made “Solo Absolu” (1992), a series focused on the genitalia of a naked male in flagrante delicto, because she “thought male masturbation was a subject not often addressed.” In her recent show at the French Institute Alliance Française in New York, a film documenting her career was not shown, she said, to shield children from the sequence. “It was not meant to be shocking.” But evidently “it still is, in 2010.”

One of Aura Rosenberg’s series, “Head Shots,” also deals with masturbation but consists of black-and-white photos of men’s faces at the moment of orgasm. The artist, who lives in New York and Berlin, says a central element of her work is to represent “a larger picture of sexuality than just women’s bodies and women’s pleasures,” and it never occurred to her not to make images of nude men. Rosenberg said she wanted the images to be “edgy, ambiguous, to reference pornography and its conventions, but not be porn.” For that reason, in “Head Shots” (selections from it published as a book in 1996), she did not photograph the obvious but relied on the expression of the face to convey ecstasy, although whether that ecstasy is real or fake is deliberately left unclear.

New York–based artist Brenda Zlamany, who began painting portraits of men in 1991 and still focuses primarily on them, says she has been criticized for her preference. “The penis is the last sacred cow, the last taboo. People tend to get stuck on one thing with male nudes—the penis—and they can’t get beyond it,” she says. “I made a full-length portrait of artist Leonardo Drew in the nude and I’ve never been able to show it. It’s too confrontational, too explosive. I have been told by certain galleries and collectors that no one really wants male nudes, but I think there are more of them around than we know about.”

Whatever the reasons, the Great American Nude, Male Edition, has yet to become an art-world staple. But if Zlamany is right, women artists need to drag the paintings of naked men out of their studios. Then maybe the next generation will feel less reticent taking up their brushes and cameras as a naked man strikes a pose. It could be revolutionary.

Lilly Wei is a New York–based art critic and independent curator.

November 2010 Announcements

KATHY BUTTERLY: The Jewel Thief / Tang Museum / Sarasota Springs, NY

RUSSELL CROTTY: Compass in Hand: Selections from Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawing Collection / originated at MOMA and travelled to Valencia, Spain / SURFER Magazine / December Issue 2010

DINH Q. LE: 2010 Prince Claus Award in Visual Arts, Amsterdam

NIRA PEREG: ARTFORUM / October Issue 2010

MICHAL ROVNER: Chevalier (Knight) Medallion, Order of Arts and Letters, France

ARLENE SHECHET: Anonymous Was a Woman Award 2010 / Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 2010

JEANNE SILVERTHORNE: Joan Mitchell Foundation Award 2010

YVONNE VENEGAS: Magnum Expression Photography Award 2010, England / Art Review, October Issue 2010

Russell Crotty Video Interview / Surfer Magazine

RACHEL LACHOWICZ / Opening Reception / November 6, 2010

RUSSELL CROTTY / SURFER MAGAZINE

“Searching for Russell Crotty”

December 2010 Issue

Mignon Nixon on Nira Pereg's Kept Alive

When Hamlet asks the gravedigger, “Whose grave’s this, sirrah?” he receives the answer, “Mine.” Nira Pereg’s three-channel video installation “Kept Alive,” 2009-10, filmed at Jerusalem’s Mountain of Rest cemetery (Har Hamenuchot) and shown earlier this year at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, similarly asks: Whose grave’s this? In Jerusalem, the question is ominously political…

RACHEL LACHOWICZ

November 6 - December 24, 2010

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to present a solo show of new work by Rachel Lachowicz. This exhibition marks the artist’s first solo show since 2005, and her twentieth year showing with the gallery.

Lachowicz is best known for her work fabricated in cosmetics, namely eyeshadow and lipstick. Iconic works such as her lipstick urinals and eyeshadow flowers appropriate images and objects created by artists of the minimal and pop movements from the 1960s and 70s. The impulse in her work has always been to relate the particular struggles of the female sphere, critiquing power dynamics between women and men in greater society; and asserting a dialogue with a specific gaze towards male artists of influence from minimalism and post-minimalism whom she respects.

The seminal performance, Red Not Blue done at the gallery in 1992 contextualizes Lachowicz’s work within the canon of feminist art. In her essay, Not: Rachel Lachowicz’s Red Not Blue, Amelia Jones frames Lachowicz as a different brand of feminist; who no longer used an aggressive voice with which previous artists from the 1980’s like Barbara Kruger commanded to critique patriarchy in society and the art world. This new brand of feminist emerging in the 1990’s, and epitomized by Lachowicz, created works which extended the dialogue with previous art histories; utilizing humor and admiration as tools while also remaining critical.

In the present body of work, Lachowicz continues to reference the feminist adage, “the personal is political”. She chooses lipstick and eye shadow as mediums for painting and sculpture about the work of women, using materials that are ever present in the daily life of a woman; and expands this dialogue with new materials. Lachowicz continues to explore feminine identity through forms of packaging. The exterior is highlighted as the means in which a woman presents herself to society, to the public. Packaging in this exhibition is quite paramount; plexiglas serves as a container to house pigment; soap molds are made in the form of packaging used in packing computer parts. Soap is used in reference to the iconic Mary Cassatt painting of a woman washing a baby. Cassatt was one of the only female Impressionist painters, who retain art historical recognition. The painting depicts a female duty; and in her soap sculpture, Lachowicz presents an homage to Cassatt; translating the feminine duty to a new era of work; perhaps something more public than private.

Rachel Lachowicz has exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Whitney Museum, Bronx Museum, Magazin 4, Bregenz, Austria, Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, France, Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Walker Art Center, Venice Biennale, “Aperto 93”, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art. She has received prestigious awards such as the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship and the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Award. Her work is represented in major collections such as the Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Whitney Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum, Museum Moderner Kunst, Palais Lichtenstein, Vienna.

For more information please contact Marichris Ty at marichris@shoshanawayne.com.

Berlin Art Link / Nicole Cohen

BASED IN BERLIN: ARTIST STUDIO VISIT

Nicole Cohen, a U.S.- born video installation artist working with video and collage, creates work which overlaps past and present scenarios, creating a sense of time travel. Using found vintage magazines, such as Brigitte and Burda, Cohen creates collages in which she cuts out the models’ faces and fills them with reflective material. Through this process, the models are given anonymity and the viewer is provoked to see themselves both figuratively and literally within these images of past mentalities and culture.

Pages of these vintage magazines are also utilized within her video installations as historic backdrops, which she layers with projected video scenes of out of places scenarios. For example, in the piece, “How to Make Your Windows Beautiful” she projects video of two young women dancing to rock music onto the cover of a home magazine which displays a bourgeois living room from the 1950s. The concept of time travel was even more present in a commissioned video installation, titled, “Please Be Seated”, where she provided the audience with the opportunity to become an active participant in the work.

Cohen exhibits internationally in various solo and group exhibitions in such locations as the Williams College Museum of Art (Williamstown, MA), the Fabric Workshop and Museum (Philadelphia, PA), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Paris, France; Shanghai, China and Harajaku, Osaka, Kobe, and Tokyo, Japan. In addition, she is the director and founder of the Berlin Collective.

From 2007-09, she exhibited “Please be Seated” at The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, California. In January 2011, she will deliver her third solo museum exhibition at the Katzen Art Center American University Museum, Washington, D.C., curated by Carolina Puente.

“Nicole Cohen’s work is positioned at the crossroads of contemporary reality, personal fantasy, and culturally constructed space. Although trained in painting and drawing, Cohen most frequently uses video as her medium, playing upon its intrinsic capacities to manipulate time, distort scale and environment, and overlay imagery. Consistently interested in engaging her audience and challenging notions of lifestyle, domesticity, celebrity, and social behavior, Cohen also uses the surveillance camera to involve her viewers in their own voyeurism. Surveillance cameras first appeared in video art installations in the late 1960s.

At a time when television dominated American culture, artists sought to change audiences from passive to active participants. In the last four decades, video art has evolved to encompass new technologies that allow for a more seamless inclusion of and reliance on the viewer for the outcome of the work, and Cohen’s projects serve as some of the most paradigmatic and successful examples.” – Peggy Fogelman, Exhibition Curator, J. Paul Getty Museum

The New Yorker / Arlene Shechet

Goings on About Town: Art

ARLENE SHECHET

The yeowoman sculptor scores with a large show of works in fired clay: visceral masses and heaped strands on brick or cracked-wood-block pedestals and stools. Some verge on the animate; others surge sideways as if in a wind or an undersea current. Bulbous vessel forms, flipped, evoke Olmec heads. Odd glazed colors tickle the eye. Intimately brawny, the show lets us in on the studio eurekas of an artist with energy and second-nature mastery to burn. Through Oct. 9.

Art Review / Yvonne Venegas

Yvonne Venegas: Maria Elvia De Hank Series

Issue 44, October 2010.

By Ed Schad

The US/Mexico Border is a supercharged issue at the moment, and Yvonne Venegas’s current photographic series is of the times: a group of large documentary photos of the life of the ‘upper class’ of Tijuana, Mexico. With access to the household of former Tijuana mayor Jorge Hank Rohn, Venegas directs her lens to the familial ordinary, from the planning of dinners and weddings to the family simply living in its surroundings. ‘How the other half lives’ photography can be terrible if the ideological hand of the photographer is played too forcefully. Fortunately, Venegas understands that for an LA viewer who knows the photographs were taken in Tijuana, thoughts of the border and problems of immigration in Mexico and the US arrive effortlessly and undidactically. Though this effect will probably diminish for audiences elsewhere, Venegas achieves enough universal human content to maintain one’s interest in her subject.

You’ll find nothing ostentatious or overplayed in Venegas’s photographs, perhaps because the ability of Rohn’s Tijuana household to achieve the outlandish is somewhat limited. For instance, the sad little swamp, Lago (2007), is far from a lush garden. Eventually the small pool will be a symbol of wealth and leisure, but at the moment it cannot but be absorbed by the poor landscape of hardscrabble Tijuana. Other Venegas photographs use a similar tactic – the family matron working intensely on a rather ridiculous, gaudy candelabra in Velas (2008), or a large party tent being constructed in the centre of a paltry dirt track in Hipodromo 1 (2006). Such misplaced attentions of wealth at play against bleak landscapes gives Venegas’s photographs a certain understated power.

Class is offered as a series of markers that separate the rich from the poor, the sophisticated from the gauche, and they are far from extraordinary. Venegas wants to connect the tiny gesture, the indicative moment, to larger issues such as wealth disparity, status and injustice. The leisure class is portrayed straight ahead and engaged in their pursuits, not immersed in any sort of decadent behaviour. Instead, a pair of stilettos on a dusty road, a bored child on a satin couch and a new fútbol stadium on the near side of a fenced boundary is enough to evoke the larger shadow of poverty hanging over this world.

The photos are laden with subtlety, restraint and empathy; their subject matter is much closer in sensibility to the early work of Tina Barney than, say, to Daniela Rossell’s Ricas y Famosas (1994–2001). The Rohn family is presumably staying put, with no need to emigrate, yet a window into their life quietly points to the vacuum that allows the disenfranchisement of millions. Often, the working poor employed by the Rohn family are noticeable in the photos, but their presence is not amplified. They are neither suffering nor happy; they simply exist in a status quo that will continue into the foreseeable future.Gallery Opening for SW2

Last Minute Intervention

September 10, 2010

Gallery opening for SW2

Last Minute Intervention

September 10, 2010

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to present the inaugural exhibition of the SW 2 initiative.

Last minute Intervention is a group exhibition featuring work by Leyden Rodriguez Casanova, David Gilbert, Nick Kramer,

Zak Kitnick, Fay Ray, Harriet Salmon, and Frances Trombly.

The exhibition utilizes a recently vacated storefront in Bergamot Station. Formerly a hair salon, the artists in the exhibition seek to address the peculiarity of the space with interventions of their work. The space is left as it recently was, leaving relics of the beauty industry behind with installed sinks and walls flanked with mirrors. The artists in the exhibition directly utilize the space, and have chosen to create and place work, which engages with the eccentricities of the space and its past usage.

PLEASE JOIN US FOR OUR OPENING TOMORROW SEPTEMBER 11th.

Looking forward to seeing you then!

Congratulations to our Artists!

Dinh Q. Lê “Living in Evolution" Busan Biennale, Korea

Zadok Ben David "Living in Evolution" Busan Biennale, Korea

Nicole Cohen “Close Encounters”, New Video Work, Rio Hondo College, Whittier, CA.

Phil Argent “Softcore HARD EDGE”, The Art Gallery of Calgary Calgary, Alberta, CA.

Mounir Fatmi Musée d'Art Moderne de Moscou, Moscou

Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, France