Join us for an artist talk Saturday, August 23, 2014 at 11:30 AM!

Please RSVP to Alana Parpal : alana@shoshanawayne.com

News

Thank you to everyone who joined us for the opening of “In-Situ”!

Art in America interviews Izhar Patkin

Interviews Jul. 07, 2014

Rendering the Veil: Izhar Patkin at MASS MoCA

by Phoebe Hoban

Izhar Patkin, Et in Arcadia Ego, 2012. Photo Gregory Cherin.

It took 10 years to develop the unique printer used to create the exquisitely rendered veils at the core of Israeli-born artist Izhar Patkin’s survey “The Wandering Veil,” on view at MASS MoCA (through Sept. 1), in North Adams, Mass. Covering 30 years of the artist’s work, the show includes several key pieces from the early 1980s, when Patkin, who moved to New York in 1977, showed with Holly Solomon Gallery. But at its heart is a collaboration between Patkin and the Muslim poet Agha Shahid Ali, who died in 2001 at age 52.

The central veil metaphor, Patkin explained in a conversation with A.i.A., came about because “we were both interested in veils, which we each had previously used in our work, and we decided that the Jew and the Muslim should meet on a veil. We saw the veil as a physical place of meeting, even though it was ethereal. It was a veil that was meant to reveal, not to hide, and then we took it from there.”

The result is a dreamlike array of ghostly chambers, each with four walls curtained with veils—pleated canvases of tulle netting printed with haunting images. Each chamber contains a bench on which rests a sheet of paper bearing the poem that inspired the images. The show begins with a brightly hued life-size sculpture in anodized aluminum of Don Quixote, reading the eponymous Cervantes novel and holding a mirror that reflects his own image, setting the stage for an exhibit that artfully—and poignantly—explores the relationship between fiction, reality and representation.

Patkin recently spoke with A.i.A. about the show at his Manhattan studio.

PHOEBE HOBAN Can you talk about what themes emerged in putting together the show?

IZHAR PATKIN Principally it was the question of the icon, the question of representation, and options other than representation, such as manifestation. By manifestation I mean a type of visual where, as in pagan religion, the statue is the god. It is not a representation of the god. It is also not an abstraction of the god. I’ve come to understand that representation and the invention of the icon were a deeply Christian phenomenon. Culturally, a very interesting question to ask is how we live under the hegemony of such a canonized idea. So one of my solutions was to turn the image, and its support structure, the canvas, into ghosts.

HOBAN What do you mean by ghosts?

PATKIN A ghost is an unresolved emotion. Once it is resolved it disappears. I think the role of the artist, the writer, is to suspend ghosts, because that suspends the emotion, the drama and the duration. I think the story of the suspended emotion or ghost that appears to take “revenge"—that is the unresolved story—is probably one of the biggest issues of culture today. We are culturally in a time when most of the works that matter are involved in some sort of cultural correction.

HOBAN Can you walk me through the show?

PATKIN The first room is based on a Pakistani poem that Shahid adapted, called You Tell Us What to Do, which is basically a complaint to God. I took that poem and placed it on the beach between Jaffa, the Arab City, and Tel Aviv, the new Jewish city, and I left all the ghosts of that conflict on the beach, as if they were all living still there, all suspended—from famous images of Holocaust survivors arriving to Palestine to today’s Palestinians on the beaches of Gaza. So there are images from different times mixed together, all as if time stood still and nothing ever got resolved.

The next room is based on the poem Violins, which repeats the word until it becomes "violence,” and I had to find a way to visually show that. My solution was to use the idea of the “theater of war,” a very strange concept. So I have the cellist Pablo Casals performing at the White House, where JFK and Jackie sit, and they are facing three other walls which have warlike scenes of armies and death and destruction.

The room called “The Veil Suite” is about Shahid dying. It’s his requiem, in which he becomes God’s bride. On two walls you have a snow scene that could be Kashmir, and then on the other two walls you have train tracks that go from one side of the room to the other, so it’s a good example of how using a room allowed me to create a visual metaphor that could not be done in a conventional painting. And you have the poet rising with the shadow of a photographer taking his picture, and on the other side you have shadows of a Jesus figure and a ballerina doing a pas de deux. The only figure in the entire piece which is actually painted is the picture of the poet.

HOBAN Can you explain the art historical references of the two last rooms?

PATKIN The room called “The Dead Are Here” is my [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard. It’s the unrequited love story of Laila and Majnoon, the legendary Romeo and Juliet of the East. She is reading his letters, which become tombstones, and he is sitting with his dog, because he stopped talking to humans. I took the format of the famous series by Fragonard, “The Progress of Love,” which happens in a glorious Parisian garden, which I exchanged for a cemetery. For the poem called Evening, my [Joseph Mallord William] Turner, I painted Venice, which for me is a place of freezing time, as in the poem, and a magical moment with Turner’s orange sky. So I have a magician sitting on a gondola releasing clouds of dark birds. He is bringing in the night, which will reignite the cycle of light.

HOBAN What about the sculpture toward the end, the porcelain Madonna cast at Sèvres?

PATKIN The Madonna gave birth to the icon. The Madonna is the icon factory—and my Madonna holds a veil, or a canvas, but it’s empty. There’s no baby there. I left it blank because it represents the moment of potentiality. And I also realized that the Madonna, this figure of motherhood, without the baby, is basically a portrait of many of my female friends who don’t have children. So I see it actually as if by strange luck I was given this very contemporary icon—today’s Madonna and child would not have a child. And from the point of view of the painter, the empty canvas is the moment of potentiality.

Artnet news on Michal Rovner

We Love Collecting … Digital Art

Astrid T. Hill, Friday, June 27, 2014

Michal Rovner Most (2011) (ed. 2/3) video/film, framed plasma screen and video.

Photo: Courtesy Ivorypress Gallery

In a recent New York Times article, writer Scott Reyburn asks: “Is digital art the next big thing in the contemporary art world?”

That depends, in part, by what is meant by “digital” art. Of course many artists, Wade Guyton and Christopher Wool among them, have already made a trend of work that is, at some stage, digitally produced. Galleries everywhere are full of paintings, prints, and photos generated digitally and then printed. The distinction here is art that is not only digitally produced but also digitally displayed, very often on-screen. And while the market for such “on-screen” work is still small, the gap between digital production and digital display seems increasingly smaller.

Last October Phillips auction house (in association with Tumblr) held its inaugural “Paddles ON!” sale in New York, consisting of 20 digital works. The auction had a sell-through rate of 80 percent. The highest amount paid for a single work was $16,000, for a chandelier constructed out of CCTV cameras by American artist Addie Wagenknecht, Asymmetric Love Number 2 (2013).

This year’s sale, which began June 21 and continues through July 3, combines an online auction via Paddle8 with a live sale at Phillips. Among the 22 featured works are digital abstracts from Amsterdam-based artist Jonas Lund, photomontages by American artist Sara Ludy, and sight and sound installations from Hannah Perry, perhaps the show’s most purely digital works, displayed on flat-screen video monitors. All of these works are estimated under $17,000 (£10,000) and most are priced far lower at about $3,400 (£2,000).

Jeff Elrod is in many ways a perfect example of an artist born of the digital age, although his techniques to some extent turn the digital paradigm on its head. He began printing computer-generated doodles, made with an old school digital drawing program, while he was a night-shift technician at the Houston Chronicle. Elrod still draws his images digitally, which he then projects onto canvas, then traces with brushes or cans of spray paint. The results are large-scale abstract paintings, which reveal their origins on a computer screen. In March and April of this year, an Elrod show, “Rabbit Ears” sold out at the Luhring Augustine Gallery, and there is currently a waiting list for his digitally-derived abstract canvases. Prices range from $50,000 to $100,000.

Artists like Cory Arcangel see a clear trend from digital production, like Elrod’s, to digital display itself. Arcangel traces the trend back—perhaps not surprisingly—to Andy Warhol and, in particular, to images Warhol made on a Commodore Amiga home computer in the mid-1980s. The images have a familiar, by now nearly traditional iconography, ranging from soup cans to self-portraits to images of Marilyn Monroe.

What intrigues Arcangel, though, is not their familiarity, but the way in which Warhol seems to have anticipated the full digitalization of art. Arcangel argues that Warhol foresaw an increasingly digitized world and that these rediscovered works from one of Pop art’s greatest printmakers already suggest an inevitable movement toward digital display.

We couldn’t agree more, which is one reason we love collecting Michal Rovner’s 2011 video installation Most.

Rovner, who was born in Israel in 1957, works in video, sculpture, drawing, sound, and installation. She has had more than 60 solo exhibitions, including a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art. In many of her works, the installation pieces in particular, history and memory intersect with contemporary politics, science, and archaeology. Most (2011) takes its inspiration from Nobel Prize–winner Wislawa Szymborska’s poem “Microcosmos,” a poem that vividly evokes the fascinations of the microscope, where biology and technology meet under the human gaze. In the video, chromosome-like figures move in pairs, split, and shift, like small creatures playing a game of hopscotch. The work, which suggests the karyotype of some hyper-advanced species, raises questions of identity, inheritance—even the fraught, ongoing history of eugenics, and, above all, the modern collision of evolving life with evolving technology. In this respect, its digitalization lies literally in the tradition of “expressing the material,” giving the piece a powerful sense of inevitability, arising from intellectual and aesthetic coherence.

It is also stunningly beautiful, a nearly archetypal representative of art’s digital future. This is why we love collecting Michal Rovner’s Most.

[Artwork featured is Maja Cule’s The Horizon (2013) HD Video loop, Blu-Ray disc 3'17" which will be offered at Phillips’s upcoming Paddles On! sale in London on July 3 with an estimate of $1,700 to $3,400]

Astrid T. Hill is the president of Monticule Art, which provides art advisory services to private collectors. She specializes in primary and secondary market works of contemporary art.

Artnet reviews Izhar Patkin at MASS MoCA

Izhar Patkin’s Poetic Enchantments at Mass MoCA

Ranbir Sidhu, Tuesday, June 10, 2014

Izhar Patkin, Time Clipping the Wings of Love (2005–11)

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

In Time Clipping the Wings of Love (2009/11), Israeli-American artist Izhar Patkin takes a Sèvres porcelain, originally an erotic setting for a clock, and transforms it through physical deformation and the random application of glaze. It’s a piece that almost disappears in this vast exhibition, “Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil,” a midcareer retrospective on view at Mass MoCA through September 1. On closer inspection, figures emerge, arms, legs, torsos, breasts, women falling somehow. Splotches of dark brown drip along the melted women’s bodies, along with sharp lines of gold.

I passed it by the first time. Fortunately, the artist, a friend, was leading me on a tour. “It’s my favorite piece here,” he said. The glaze, when he applied it, was invisible, and so he had no real idea how it would turn out after firing. Splotches of dark brown dripped down along the mostly melted women’s bodies, along with sharp lines of gold. If he did it again, he laughed, he’d make it even uglier.

This tension, between the ugly and the beautiful, between the mundane and the profound, is on display throughout this sprawling show, which extends over two vast levels of the museum.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

The Messiah’s glAss (2007)

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

The Messiah’s glAss (2007) tackles questions of orthodoxy and messianism in contemporary Israel. The decapitated head of a donkey, cast in glass, is set atop a glass table. A pair of stylized glass testicles hang below the table’s surface, as if its legs were the hind legs of an animal. The piece draws on imagery from the Book of Zohar, where the donkey becomes an image of Satan, and later Jewish theology, in which the so-called “Messiah’s Ass Generation,” lost to God and sunk in debauchery, is believed to usher in, by their extinction, the age of the Messiah.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014).

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

The heart of the show, filling one of the massive main galleries, is the American premiere of Patkin’s longstanding collaboration with Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali. Five rooms have been constructed, each walled with paintings on undulating and often overlapping tulle curtains.

Each room was inspired by a poem by Ali. In one, The Veil Suite, the poet wrote a text specifically for Patkin to work from. Here, the figure of Jesus on the cross dances en pointe with a ballerina on railroad tracks that stretch arrow-straight to the horizon. On the opposite wall, on different railroad tracks, a man stands with his face hidden in a prayer shawl while a photographer crouches under an old-style camera’s hood to take his photograph. The mountains which circle the scene could as easily be in Colorado or the Himalayas.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

The Dead Are Here. Listen to the Survivors

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

In one of Patkin’s most gorgeous rooms, based on the poem by Ali, The Dead Are Here. Listen to the Survivors, a riot of spring colors brings to life a cemetery garden. In the image, a young woman leans her back against a statue’s pedestal while reading a book and a man lies on the grass next to his sleeping dog. White, unmarked tombstones stretch into the distance. The warmth of the day is palpable.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

Don Quijote Segunda Parte (1987)

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

Another towering sculpture, Don Quijote Segunda Parte (1987), greets visitors at the exhibition’s entrance, showing the famous knight sitting astride his horse and reading a book of his own adventures while admiring himself in a hand mirror. Taken from an anecdote in Cervantes’s second volume, which humorously acknowledged that in the years since the first book of Don Quixote, others had sought to continue the knight’s tale, it brings to the surface questions of authenticity, the self, narrative, and the curious art of storytelling.

In its circularity, the knight’s vainglorious self-regard, where an imaginary figure reads invented tales about himself, we find a mirror for the tensions that illuminate much of Patkin’s work. Narrative, performance, the self and its creations, are seen in constant and ever-shifting flux. To look for answers here, Patkin suggests, is a fool’s errand, but to ask questions, and to continue asking them, though not a path to redemption, can lead to ever more refined ideas about the possibilities of being.

Ranbir Singh Sidhu is the author of Good Indian Girls and the winner of a Pushcart Prize.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014).

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

Michal Rovner in the LA Times

Review Michal Rovner charts ghostly migrations

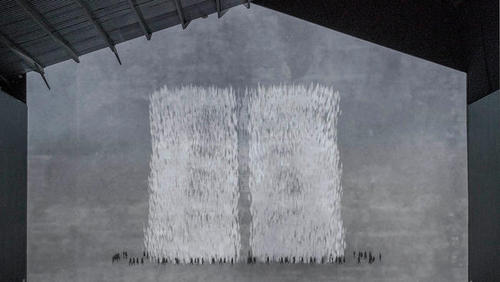

Michal Rovner, “Current Cross,” 2014. Video projection. Audio composed by Heiner Goebbels. (Gene Ogami)

By SHARON MIZOTA

In Michal Rovner’s latest exhibition at Shoshana Wayne, the darkened main gallery becomes a cavernous, hushed space — like a chapel or perhaps a tomb — dominated by the elegant, wall-size video projection “Current Cross.”

It features two large, white rectangles composed of pulsing feathery marks that slowly merge into one and then divide again. Along their bottom edges, a steady stream of tiny black figures makes a ragged procession around the two chalky shapes.

Examined more closely, the shapes are also composed of thousands of little white ambulatory figures. Already elegiac, the rectangles are in fact teeming with ghosts.

This theme is echoed in a smaller projection onto 11 slabs of black limestone. Here, tiny figures crisscross a barren landscape, continually bridging the gaps in the stones, some of which are also covered with the waving silhouettes of cypress trees.

This migratory motif also appears in a group of six ingenious video “paintings,” each spanning two LCD screens butted against each other. Rovner cleverly uses the cypresses to disguise the screen’s hard black frames; the trees simultaneously divide and unite the rocky landscapes.

Rovner was born in Tel Aviv, and it’s hard not to read these images as a kind of Israeli mythology. However, by keeping the figures tiny and nondescript and the landscapes abstract, she has created images resonant of all kinds of displacement. We have all felt like wanderers at some point, trudging we know not where.

Shoshana Wayne, 2525 Michigan Ave. B1, Santa Monica, (310) 453-7535, through July 12. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.shoshanawayne.com

Copyright © 2014, Los Angeles Times

Michal Rovner featured on KCRW's Art Talk

If you’ve ever stood in front the famous 2,000-year-old Rosetta Stone at the British Museum and fantasized what it would be like to not only read its inscriptions in three different languages, but also to hear these languages spoken and even to see it in the process of being written, then, my friends, I have an adventure for you that will turn all these fantasies into reality.

Michal Rovner, “Current Cross,” 2014

Video Projection

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Internationally recognized Israeli-born artist Michal Rovner is having her third solo show at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Working in such diverse media as photography, painting, sculpture, sound and installation, Rovner is particularly celebrated for her video work.

Michal Rovner, “View,” 2014

LCD screens, paper and video

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Photo Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Entering the vast, darkened space of the gallery, one slowly approaches the back wall while staring at its softy glowing black and white video, Current Cross 2014, trying to make sense of its semi-abstract shapes, which brings to mind the iconic compositions of Mark Rothko. To understand and fully enjoy Rovner’s videos, one needs to slow down and stay quiet for a while. That is the way to get them. And by “to get them” I mean not only to see it and to hear its mysterious whispering audio, but also to become aware that what, at first impression, appears to be tiny inscriptions etched into stone, are actually silhouettes of human figures. Hundreds of them. One cannot say whether they are male or female, or what culture and religion they belong to. They are humans. They are us.

Michal Rovner, “Broshei Laila,” 2012

Black limestone and video projection

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

In the same main gallery, there is another show-stopping video by Michal Rovner, Broshei Laila, 2012. But this one is projected onto eleven slabs of black limestone. The wide, nighttime landscape is interrupted by dark silhouettes of Cypress trees, looking like exclamation points demanding our attention. And once again, hundreds of tiny white and black silhouettes of human figures are slowly marching through this biblical landscape.

“Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye”

Works from the Gordon W. Bailey Collection

Exhibition at LACMA

In a small adjacent gallery, a few more videos of Rovner’s work are shown on medium-sized LCD screens. In these videos, the artist continues her exploration of landscapes with the Cypress tree and tiny marching figures, but this time she incorporates much bolder colors. Ultimately, it’s up to us, the viewers, while looking at these videos to decide what exactly we are looking at? The pages of the New or Old Testament? Or perhaps at the pages of some other ancient manuscript?

Sam Doyle, “Gulf 7c,” 1982-1985

House paint on wood

Gordon W. Bailey Collection

“Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye” exhibition at LACMA

Now, let’s travel back to the 20th century and zero in on a singular figure –– the favorite subject of Sam Doyle (1906 – 1985), an amazingly talented self-taught African American artist from the South. The small but well focused exhibition of his paintings is currently on display at LACMA, where it’s tucked away in a small gallery on the third floor. All works are from the private collection of Gordon Bailey. A few months ago, I talked about some of Doyle’s works at the exhibition, Soul Stirring, at the California African American Museum in Downtown LA. Though painted with house paint, often on discarded metal roofing, his compositions are surprisingly elegant and his choice of color would make even Matisse pay attention. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that among collectors of Sam Doyle’s works are such artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Ed Ruscha.

“Ashes and Diamonds,” 1958, Poland

Directed by Andrzej Wajda

Photo Courtesy MoMA

Let me end with a message to all of you, my smart and curious friends. There are a surprising variety of interesting things happening at museums besides their important exhibitions. So you might want to pay attention. Last week, I went to LACMA for the rare screening of Ashes and Diamonds (1958), the seminal movie by Polish director Andrzej Wajda –– astonishing cinematography and heartbreaking story of the last day of World War II.

Space Shuttle Endeavour

California Science Center

Then I attended a fundraiser for artworxLA with its programs to combat LA’s high school drop-out crisis. It took place at the California Science Center, and we were seated under the wings of the suspended Space Shuttle Endeavour. It takes a special occasion to make me speechless and this was one of them. Wow wow wow… And to top it all off, there was a Saturday night concert at the Getty Center by William Tyler, a Nashville-based guitar player, whose acoustic guitars drove the audience wild.

Banner image: (L) Michal Rovner, Shomron, 2012. LCD screens, paper and video. © Michal Rovner, View, 2014. LCD screens, paper and video. ® Michal Rovner. Yaar (Laila), 2014. LCD screens, paper and video. Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Other photos by Edward Goldman, unless otherwise indicated.

OPENING TOMORROW:

MICHAL ROVNER

Nofim

May 10-July 12, 2014

Reception May 10, 2014 5pm-7pm

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to present Nofim, a new exhibition by Michal Rovner. This is the artist’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. Working in video, sculpture, drawing, photography, painting, sound, and installation, Rovner begins with reality and creates situations that illuminate themes of change and the human condition.

With imagery taken from Israel, the landscapes and figures are at once familiar and foreign, calming and disconcerting, personal and political. The figures sway and move yet they do not escape the scene. The scenes are ambiguous enough as to refuse definitive identification yet they are familiar enough as to evoke deep visceral connections.

The power of Rovner’s work rests in her ability to evoke visceral responses to her art. Her landscapes are stripped down, fragmented, and homogenized in such a way that they could be almost any mountainside, desert, or ocean. The human figures are abstracted so as to blur distinctions not only between male and female but also between nationalities –humanity in its most essential form. The cypress trees that are central in this particular body of Rovner’s work, have varied and rich cultural significance worldwide. In the Mediterranean region, it is one of the most ancient trees with scholars noting its presence in biblical writings. In Greek and Roman culture, the cypress symbolizes mourning and hope. For Rovner’s purposes, it is not the cypresses inscribed meanings that are significant, but it is the fact that they exist in the landscape. They are tangible and real marks that either cut or mend a particular scene and the ways they move in Rovner’s work insist upon fluctuation and instability.

In the main gallery, there are two projections. On the East wall Current is projected onto a painted surface. On the West wall Broshei Layla is projected onto eleven slabs of black limestone. While each slab is individually cut, the imagery projected onto them connects each piece while at the same time underscoring their separateness. In this way Rovner subtly shifts the viewer’s attention from implications of archaeology to geopolitical divisions/fragmentations.

In the smaller gallery, there are five of Rovner’s screen works each composed of LCD screens, video, and Japanese paper. These works present barren and ambiguous landscapes, cypress trees and occasionally human figures.

Michal Rovner was born in Tel Aviv, Israel. She lives and works in New York and Israel. Her work has been exhibited extensively worldwide in over 50 solo exhibitions, including exhibitions at prestigious venues such as the Israeli Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Living Landscape (2005) at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, the Jeu de Paume, the Louvre, and a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York.In June 2013, Rovner’s Traces of Life: The World of the Children opened at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Among many awards and honors, in 2008 Rovner received an Honorary Doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and in 2010, she was honored with the Chevalier (Knight) Medallion of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France.

For more information, contact Alana Parpal at alana@shoshanawayne.com

Kathy Butterly featured in CFile Online

Exhibition | Kathy Butterly: Little Sexual Beasts at Tibor de Nagy

John Yau, in beginning his review of the deliciously sexy show by Kathy Butterly at Tibor de Nagy (New York February 27 – April 12, 2014), gives a partial list of ceramics exhibitions at major New York galleries over the past 12 months:

“Ken Price: Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (June 18–September 22, 2013), which I reviewed for Hyperallergic Weekend; Joanne Greenbaum: Sculpture at Kerry Schuss (May 2–June 2, 2013); Betty Woodman: Windows, Carpets and Other Paintings at Salon 94 Freemans (May 7–June 15); Alice Mackler: Sculpture, Painting, Drawing at Kerry Schuss (June 9–July 26, 2013); Arlene Schechet: Slip at Sikkema Jenkins (October 10–November 16, 2013); Mary Frank, Elemental Expressionism: Sculpture 1969–1985 & Recent Work at DC Moore (November 14–December 21, 2013), for which I wrote the catalogue essay; Lynda Benglis at Cheim and Read (January 16–February 15, 2014).

“Current exhibitions include: Jiha Moon: Foreign Love Too at Ryan Lee (February 1–March 15); Norbert Prangenberg: The Last Works at Garth Greenan (February 27–April 5, 2014), for which I also wrote the catalogue essay; and Kathy Butterly: Enter at Tibor de Nagy (February 27–April 19, 2014).”

To this he could have added Edmund de Waal at Gagosian, Robert Arneson at David Zwirner, Gareth Mason at Jason Jacques, Takuro Kuwata at Salon 4 and a few dozen more. Indeed, the 2013-14 art season has been a bumper one for kiln fruit.

It is instructive that Yau offers this list within Butterly’s review because this artist, a student of Robert Arneson, was a trailblazer crossing over into the fine arts with her porcelain vessels soon after graduation and being hailed as one of the City’s most important emerging artists by New York Times critic Roberta Smith.

In a review for her previous exhibition at Tibor de Nagy, Panty Hose and Morandi, Butterly is compared to George E. Ohr (1857-1018) the radical Biloxi potter:

“Kathy Butterly’s current show, Enter, at Tibor de Nagy confirms what I first thought when I reviewed her previous solo show, Panty Hose and Morandi, at the same gallery for the Brooklyn Rail:

“The formal traits she shares with Ohr include a penchant for crumpled shapes, twisted and pinched openings, and making (as Ohr was understandably proud to point out) ‘no two alike.’ Working within the confines of the fired clay vessel, Butterly has transformed this long established, historical convention into something altogether fresh and new, melding innovation to imagination so precisely that it is impossible to separate them.”

This is relevant and obvious. Less apparent and more subversive is her love of Ken Price’s work and the sexual energy one finds in both these artists.

Moreover, Butterly is able to make the miniature monumental. The forms are small, yet labyrinthian; her aesthetic ambition is vast and sprawling. As Yau notes:

“While maintaining a modest scale, she continually reinvents the fired clay vessel (cup or vase) in ways that exceed anything anyone else has done in the medium. From the unique base to the distinct body (creased, collapsing, convoluted and twisted), to the diverse surface, which can run from smooth to craqueled, often in the same piece, to the saturated color (sunshine yellow, fleshy pink, Veronese green and fire engine red), to minute details (yellow lozenges the size of an elf’s pat of butter), everything (including the spills and stains) in a Butterly sculpture attains its own particular identity.”

He continues:

“Butterly’s commemorations of misshapenness contradict a basic assumption in ceramics and, by extension, art, which is it is possible to make a perfect or ideal form, achieve a timeless beauty. The postmodern converse of this ideal, that one can make a perfect corpse (or copy), is well known. Butterly doesn’t buy into these models, with their roots in Plato (the ideal) and Aristotle (classification). Rather, she seems to believe that change is central to experience. In shaping her vessels, she folds, bends and twists the clay, recognizing that anxiety, worry and vulnerability are inherent to existence. Unable to escape time and the constant, multiple pressures it applies, she transforms those forces into contours and forms that are simultaneously goofy and shy, fantastic and disenchanted, gaudy and thwarted, sexy and monstrous.”

The string of pearls, a continuing motif for Butterly, is still with her. One sees this in Scout, almost invisible, minute white beads frame the foot. This fetish jewelry with a thousand sexual connotations is, as I once said when interviewing Butterly in front of a (shocked) Philadelphia audience, is as much a sexual toy as the dildo.

It is liberating to feel her libidinal empowerment as a woman. She is not coy about this. The projection of eros in the art is funky, frank, open, pleasure-seeking and persistent, blending seamlessly with liquid sensuality of her medium.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile.

Above image: Kathy Butterly, Dual 2, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 6/8″H x 5 3/8″W 3 6/8″D. Photograph courtesy of the gallery.

Left: Kathy Butterly, Color Hoard-r, 2013, clay, glaze, 5″H x 3 3/4″W x 3″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, Diptych, 2014, clay, glaze, 5 1/8″H x 6 1/4″W x 2 7/8″D

Left: Kathy Butterly, Loud Silence, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 3/4″H x 4 3/4″W x 4″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, Wanderer, 2013, clay, glaze, 6 1/8″H x 6 1/8″W x 6 1/4″D

Left: Kathy Butterly, Jersey Poe, 2013, clay, glaze, 6″H x 5 3/4″W x 5″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, High Life, 2013, clay, glaze, enamel paint, 8 3/8″H x 7 3/4″W x 7″D

Kathy Butterly, Glacier,2013, clay, glaze, 6 7/8″H x 6 3/8″W x 4 1/4″D

Kathy Butterly, Loud Silence, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 3/4″H x 4 3/4″W x 4″D

Kathy Butterly, Scout, 2013, clay, glaze, 3 7/8″H x 5 3/4″W x 3 7/8″D. All photographs courtesy of the gallery.

Artforum - Beverly Semmes talks about her work!

Beverly Semmes

02.05.14

Beverly Semmes, Pink Pot, 2008, paint on magazine page, 7 ½ x 10 6/8".

Beverly Semmes is a New York–based artist who has exhibited internationally since the late 1980s. Her latest shows span the US: Los Angeles’s Shoshana Wayne Gallery is presenting two of Semmes’s large-scale dress works, produced in 1992 and 1994, from January 11 to March 1, 2014. In New York, Semmes will show selections from her ongoing Feminist Responsibility Project, as well as ceramics, at Susan Inglett Gallery from February 6 to March 15, 2014.

IN THE EARLY 2000S, I inherited a stack of 1990s-era porn magazines. It’s a long story in itself, but basically I was helping a friend in upstate New York who wanted to get rid of them but was too embarrassed to take them to the town’s recycling center. I took them home. Not long after, I was working in my studio and I thought: I need these. As I was cracking them open, I had the idea to get some paint out. The first pieces were essentially cover-ups—fluorescent censorships. This is how the Feminist Responsibility Project began. I wanted the FRP works to have a protective aspect: protective to the viewer, protective to the subject. The covering up is nurturing—in a grandmotherish way—and it’s complicated. The redactor is spending a lot of time with the imagery, censoring to keep you from getting/having to see the original material. The images break out of the control: There are rules, but these codes keep getting broken and content slips forward.

I’m often putting this body of work to the side while I focus on another project, but then I end up returning to it. At this point it’s been more than ten years, and I’ve made hundreds. They’ve taken on a painterly surface; they are structured in response to the absurdly concocted magazine scenarios. I make these drawings at the kitchen table. There’s a lot of editing afterward. I’m rethinking and reworking them all the time. There will be pieces in the “not working” category that later become my favorites. It evolves.

I recently installed my show at Shoshana Wayne in Santa Monica—the main gallery is an expansive rectangular space—and the 1994 piece I’m showing there, Buried Treasure, fills the room. Re-seeing this work after many years, I was struck by how much of a drawing it is. There’s one long sleeve and it drapes around the floor. The black crushed velvet is very light-absorbing; it has an oily burnt wood quality, a superblack, like vine charcoal. Many of my sculptures from the ’90s were designed to take up space. The viewer is pushed way to the side; you can’t really walk into the room. Like the FRP, there is a graphic sensibility to my sculptural work of this time. The Feminist Responsibility Project is more intimately aggressive.

As the Susan Inglett Gallery show in New York approaches, I continue to ask myself about the relationship of the drawings to my ceramics. The question has been hanging over my head for at least five of the ten-plus years I’ve been doing the FRP drawings. Ceramics has been my most consistent medium—the one I continue to return to. I began working in clay right after I finished school. The pieces are hand-built. I begin with a lot of very wet clay and then build them up over time, adding handles. They are heavy and off-kilter, and there’s no goal of perfection or lightness as with traditional craft. The glaze has a skin-like aspect; the works are extremely tactile. The ceramics enter into the gallery space as outsiders, as “anti-,” and on some level I’ve always thought of the FRP drawings as doing the same.

— As told to Lauren O’Neill-Butler

Izhar Patkin at Mass MoCA - The Boston Globe

At Mass MoCA, a return from the shadows for Izhar Patkin

By Jeremy D. Goodwin | GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JANUARY 18, 2014

“I’m still alive, alive to learn from your eyes

that I am become your veil and I am all you see”

— Agha Shahid Ali, “The Veiled Suite”

NORTH ADAMS — Sitting over a cup of rice-and-lemon soup in the cafe at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, Izhar Patkin is describing the car accident he’d had a few weeks prior. Headed back to North Adams to finish installing his massive new survey show at the museum after a Thanksgiving respite, the Israeli-born painter and sculptor flipped over his car on the icy Taconic State Parkway, totaling it.

“I thought I was going to die, and I had two thoughts,” he recounts. “I was glad I was alone. Death is personal. It’s nobody else’s business — like going to the bathroom. Then I had the petty thought: They’re going to have to finish writing those wall panels without me.”

For Patkin, musings on eternity mix easily with talk of his show’s details. And his thoughtful, even brooding exterior can lighten quickly for a sarcastic aside or a quick burst of self-consciousness. It fits that his recent work displays an ever-present awareness of death, tinged with darkly cheeky gestures. Patkin appears to have taken his experience in stride, and he has a dramatic new tale to tell.

“Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil,” on view through Sept. 1 at Mass MoCA, caps a return from the shadows for this artist, whose early breakthroughs included a full gallery devoted to his attention-grabbing paintings on black neoprene curtains at the 1987 Whitney Biennial.

This is not only the largest exhibition yet assembled from Patkin’s flamboyantly eclectic mixed media works. (A co-presentation with the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Open Museum in Tefen, Israel, it appeared overseas in bifurcated form in 2012.) It’s also the public’s first extended look at the work Patkin, 58, has quietly created throughout a decade of relative silence.

He’d been a busy art-maker on the rise after moving to the United States in 1977, seeing his work collected by the Whitney, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and other resume-sweetening institutions.

But shortly after the 9/11 attacks, he was stunned by the deaths of several people close to him, all within a year: his father, his best friend and her husband, his longtime art dealer and confidante Holly Solomon, and the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali, with whom he’d struck up a deep friendship and creative collaboration. Patkin quietly dropped out of the art scene, retreating to the sanctuary of his rambling East Village apartment and studio, an urban oasis hewed from a former vocational school.

“It wasn’t a decision,” he says of his inward move. “I just sat in the garden and started taking to the ghosts.”

Now he’s emerging. And he’s been busy.

The centerpiece of the exhibition at Mass MoCA is a suite of new works — five “rooms,” each formed by four hanging sheets of bridal illusion fabric, the stuff of wedding veils. Up to 25 feet long, each is a panel in a wrap-around mural inspired by the poetry of Ali, who was a finalist for the National Book Award in poetry the year of his death. (Ali is buried in Northampton; in his final years, he was director of the MFA program in creative writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, among other academic posts.)

The show also samples generously from Patkin’s earlier work, including startling mixed-media essays that seem to overflow with intertextual references. There’s his colorful blown-glass sculpture of the Hindu goddess Shiva, laced with visual nods to Josephine Baker and Carmen Miranda. (The piece is on loan from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s collection.) There’s a barn wall with a window to nowhere, adorned by a painted scene inspired by both a Franz Kafka story and Pennsylvania Dutch folk art. An oil portrait of a childless Madonna is rendered on wire mesh, its paint casting a shadow on the wall behind.

“There’s an amazing list of materials he uses — anodized aluminum, shadow puppets, video, wax, porcelain,” observes Mass MoCA director Joseph Thompson. “But his subject matter doesn’t move all that much, even though the materials change a lot. I think the nature of fiction and how we represent ideas is really his core interest.”

The new works, collected under the title “Veiled Threats,” are fantasias inspired by Ali’s poetry, as well as by Patkin’s family history and the history of Israel. The artist refers to them as paintings, though he commissioned the invention of a special printer to fashion the images in ink from digital collages.

“It was simply breathtaking, and I think I was mesmerized because I kept on going ’round and ’round and I couldn’t leave the room,” says the late poet’s brother Agha Iqbal Ali, who brought his father and a sister to see Patkin’s take on the poem “The Veiled Suite” in Patkin’s studio shortly after it was finished. He recalls the visit over the phone from a Qatar hotel. “The emotional thing for me is that Shahid died much too young. So when I see this kind of work, I say: What would not have been possible if Shahid had not died?” he remarks, paraphrasing a line of his brother’s poetry.

The veil pieces are crowded with shadowy figures. A magician conjures a flock of pigeons. The crucified Jesus, in a sort of cosmic duet with a ballerina, appears lain across train tracks. “Arik Patkin WTC” includes a photograph of the artist’s father in front of the World Trade Center, taken in August 2001; the bench on which he sits hovers mysteriously.

A sense of the uncanny is heightened by the medium of the veils; the images seem to break apart, or come into better focus, as the viewer moves around the room. The essence always seems suspended between two states. The ghosts are present.

“The dead are very persistent. They don’t leave so easily,” Patkin says, sitting on a stool in his kitchen at home. The shelves there still hold spices that Ali requested Patkin buy, for vindaloo dishes he’d cook as the two got to know each other, exploring a collaboration suggested by a book publisher.

A few feet away lies the courtyard garden where Patkin later made a daily custom of sitting alone, addressing his departed friends and family. At that time he mused deeply on the relationship between reality and illusion, and the notion that unresolved emotions become ghosts — perhaps literally.

“Before I made the veils, I had a deep trepidation,” he says. “I thought, I’m going to make these veils and they’re going to become so material and be so ghostly that once I make them there will be no way back. And I actually thought I will go crazy once they are made.”

He’s been spared that fate; he says the launch of this exhibition instead allowed him finally to let go of this body of work, over which he brooded for so long.

Though “The Wandering Veil” was prefaced by much more modest shows at the Jewish Museum in New York and the Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Los Angeles in 2012-13, it arrives now as an emphatic reintroduction of Patkin to a public that may have lost sight of him for a while.

“I think what would be so important about the show in North Adams is people in the States will see what he’s been up to,” says Nancy Spector, chief curator at the Guggenheim and a longtime friend and advocate of Patkin. “In Israel he’s a kind of national treasure in a sense, but it’s great for people here to know him, and certainly a younger generation that wasn’t going to galleries in the ’80s, didn’t see the [1987] Whitney Biennial, didn’t know what he was doing in the East Village. I think it’s a great occasion.”

Jeremy D. Goodwin can be reached at jeremy@jeremyd goodwin.com.

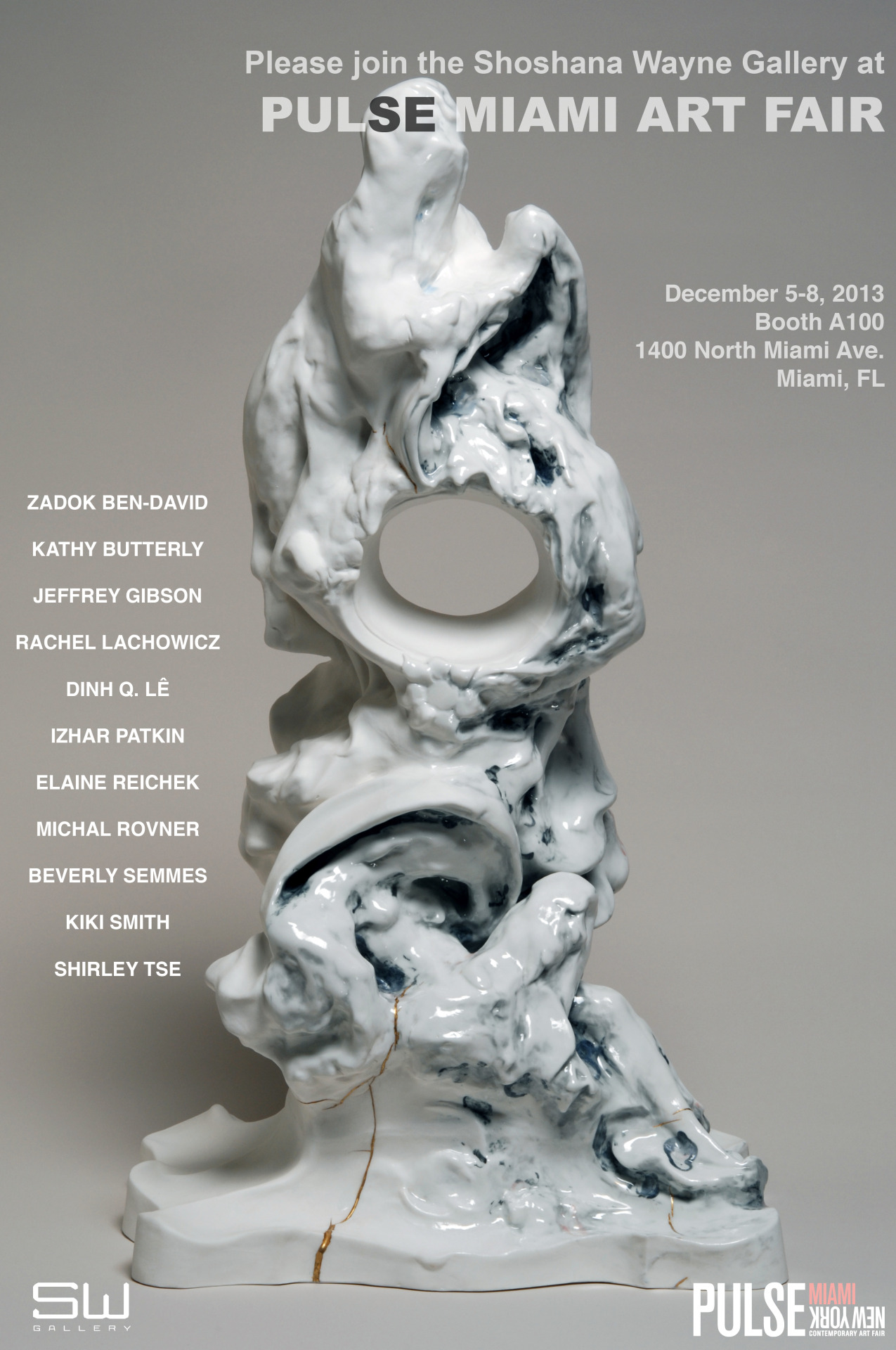

PULSE Miami 2013

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to invite you to visit Booth A-100 at PULSE Miami, Thursday, December 5th through Sunday, December 8th. A select group of works by Zadok Ben-David, Kathy Butterly, Jeffrey Gibson, Rachel Lachowicz, Dinh Q. Lê, Izhar Patkin, Elaine Reichek, Michal Rovner, Beverly Semmes, Kiki Smith, and Shirley Tse will be on view.

Rachel Lachowicz featured in the LA Times

Review: Rachel Lachowicz gives gender roles an intriguing makeover

Rachel Lachowicz’s “Particle Dispersion: Hex Triplet Pink,” 2013, Plexiglas case with eyeshadow. (Gene Ogami / Shoshana Wayne Gallery)

By Sharon Mizota

4:30 PM PST, November 14, 2013

In her latest exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Rachel Lachowicz continues her exploration of gender roles in an unusual medium: makeup.

That choice is an unavoidable statement about gender, like Janine Antoni painting the floor with her hair dipped in Clairol, or the fact that knitting and embroidery — now ubiquitous in museums and galleries — still carry connotations of “women’s work.”

Lachowicz’s challenge is to do something interesting with a medium that comes with so much baggage. For the most part she succeeds, although at times the work can be formulaic.

The Santa Monica artist uses small, square cakes of eye shadow like mosaic tiles to create “paintings” of text and scientific phenomena. The text works, executed in a Baldessarian, sign-painter style, are perhaps a bit glib. One, a riot of colors, declares, “TRUE COLORS,” even though makeup is anything but.

Another uses shades of black, white and gray to encourage us to recombine the letters in “CONTEXT IS QUEEN” in various ways. (“Conque” is apparently some kind of software plug-in as well as a Spanish-language conjunction. Who knew?) I suppose the work feminizes the notion that context is everything, although I found it puzzling.

The show gets more intriguing when Lachowicz tackles the male-dominated field of science. “Quantum Dot with Two Electrons” is an image of a red and yellow oblong shape enclosing two white-hot centers against a flat black background. The collision of quantum physics, in which particles may occupy multiple locations at once, and makeup, in which things are often not as they seem, creates a provocative parallel between two disparate worlds.

Lachowicz also takes on geology in a series of sculptures. Arrayed across the floor in the main gallery are several large, angular, Plexiglas boxes. Tinted in neon colors, they are filled with eye shadow, this time in its loose, powder form. The sculptures resemble geodes, crystals or perhaps even gems (a girl’s best friend?), but are patently artificial, like cartoon versions of rocks. Still, their powdery innards remind us that most pigments are minerals: Why shouldn’t the rocks get a makeover?

Finally, Lachowicz turns her eye to astronomy. “Cosmos” is a richly illustrated map of constellations and planets labeled with words like “evolve” and “post-gender.” It’s corny and a tad simplistic, but its heart is in the right place, suggesting a remapping of relationships and definitions.

It’s intriguing to see this theme explored within the somewhat limited commercial palette of makeup, which has not always been a feminist’s friend.

Yet Lachowicz has created a space in which former opposites are held in tension: natural and artificial, female and male. Like electrons, they might trade places, or better yet, occupy the same space at the same time. And putting on makeup might not be just an artful, conformist lie but an evolution of sorts.

Shoshana Wayne, 2525 Michigan Ave., B1, Santa Monica, (310) 453-7535, through Dec. 21. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.shoshanawayne.com

Dinh Q. Lê and the 2013 Carnegie International in the New York Times

Art Review

The Carnegie International Keeps Its Survey Small

By ROBERTA SMITH

Published: October 10, 2013

PITTSBURGH — The 2013 Carnegie International is a welcome shock to the system of one of the art world’s more entrenched rituals. This lean, seemingly modest, thought-out exhibition takes the big global survey of contemporary art off steroids.

With only 35 artists and collectives from 19 countries, the latest Carnegie says no to the visual overload and indigestible sprawl frequent to these exhibitions. It also avoids the looming, big-budget showstoppers — aptly called festivalism by the critic Peter Schjeldahl — for which they are known. Actually, the Carnegie all but leaves festivalism at the door: “Tip,” the immense, shambling, cheerfully derivative barrier of wood, fabric, cement and spray paint by the British sculptor Phyllida Barlow, just outside the museum’s main entrance, is probably the show’s biggest single art object. Inside, almost nothing on view dwarfs the body, addles the brain or short-circuits the senses. It’s just art. Did I mention that half of the artists are women?

The 2013 Carnegie has been organized by Daniel Baumann, the director of the Adolf Wölfli Foundation at the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, and Dan Byers and Tina Kukielski, two Carnegie curators. It may contribute to its deviation from convention that the curators have little experience with big surveys and don’t belong to the international curatorial cartel that circles the planet.

Their selections often evince a gratifying affinity for color, form, beauty and pleasure, and a lack of interest in finger-wagging didacticism. They have appended to their show an impressive newly installed display of Modern and contemporary works from the museum’s permanent collection that highlights acquisitions from the previous Carnegie Internationals (and includes a boxy, tilted, very red and much stronger piece by Ms. Barlow).

The show itself accounts for much of the tangled strands of today’s art, with emerging artists under 35 in the slight majority, and somewhat older ones adding ballast. There is space for occasional mini-retrospectives, including a sizable gallery filled with nearly 35 years of text pieces, photo works and bright, diminutive riffs on Russian Constructivism by the mercurial Conceptualist Mladen Stilinovic. A group of 19 increasingly robust paintings by Nicole Eisenman traces the evolution of her incisive reinterpretations of early Modernist figuration and mingles with new plaster sculptures. For example, “Prince of Swords,” a large male figure with hands blackened by an overused smartphone sits on a plinth usually occupied by plaster casts in the museum’s collection.

A cache of 57 undulant visionary landscapes by the American Joseph Yoakum (1890-1972) and 10 finely textured, scroll-like drawings of phantoms by the Chinese Guo Fengyi (1942-2010) — both formidable outsider artists — are included as if it were no big deal. The distinction was rendered moot by the extraordinary insider-outsider pileup of “The Encyclopedic Palace” at the Venice Biennale. Yoakum may qualify as the greatest artist in this Carnegie simply because his art has stood the test of time the longest.

Outstanding among the less familiar artists are two Iranians. In the 1960s and ’70s, especially, Kamran Shirdel (born in 1939) made effortlessly structural, quietly subversive films, intended as propaganda, that were often banned by both the regime of the Shah, which commissioned them, and that of its Ayatollah successors. Rokni Haerizadeh, 40 years younger, lives in exile in Dubai and has an unerring gift — shaped by Persian painting and perhaps by Goya and Art Spiegelman — for reworking found photographs into disturbing, if often beautiful, animations. His subjects here include the 2009 Iranian demonstrations and Britain’s latest royal wedding.

Less expected is “The Playground Project,” a show-within-the-show organized by the Swiss writer and urban planner Gabriela Burkhalter. Its dense history of postwar playground design — possibly better as a book — culminates in a wonderful assortment of art from the Carnegie’s annual art camp for children. This summer’s used teaching plans devised by the artists Ei Arakawa and Henning Bohl, who also contribute a playground-focused video. Though the Carnegie has no stated theme, the excellent catalog places emphasis on play as essential to art and life; “The Playground Project” gives liberating experiential form to its thesis.

This Carnegie International exposes the supposedly great divide between object-oriented or, as some would have it, market-driven art, and activist, socially involved art and suggests that they are not nearly as mutually exclusive as often supposed. To one side are the audacious computer-generated abstract canvases of Wade Guyton and the equally innovative handmade plaster and casein tabletlike abstractions of Sadie Benning, as well as the richly colored sculptures of Vincent Fecteau, which negotiate a new literally convoluted truce between the organic and the geometric.

On the other are Mr. Arakawa and Mr. Bohl’s art-camp collaboration and the especially inspiring social activism of Transformazium, a three-woman collective that relocated to Braddock, just outside Pittsburgh, from Brooklyn six years ago, determined to make a difference. Their latest effort, part of the Carnegie show, is a permanent art-lending service in the library of this recovering town, stocked with works donated by the other artists in the Carnegie, local residents and Transformazium friends across the country.

But the exhibition repeatedly illuminates the ground where form and activism overlap. In addition to the films and animations of Mr. Shirdel and Mr. Haerizadeh, this area includes Zoe Strauss’s small, remarkably lively color photographs of local residents in Homestead, another struggling Pittsburgh-area town. Also here are Zanele Muholi’s imposing black-and-white photo portraits of South African lesbians and transgendered people, and the striking welded steel assemblages of Pedro Reyes, from Mexico, which turn out to be amazing percussive instruments, even as you realize that they’re made from deactivated guns. Henry Taylor’s implacable paintings of African-Americans and Sarah Lucas’s stuffed-pantyhose sculptures of brazen women are confrontational in both medium and message.

This exhibition attests to the health of object-making of all kinds and also to art-oriented activism, as in the Arakawa/Bohl art classes and Transformazium project — suggesting that play is the crucial, underlying connection. But it points up the hazards, if not laziness, of curatorial intervention and appropriation of other artists’ art. Paulina Olowska has put on view some puppets from a once-flourishing Pittsburgh puppet theater; their intensity makes her photo-based paintings look wan. Gabriel Sierra paints the museum’s Hall of Architecture deep purple to little effect, other than evoking the Brooklyn Museum’s installation missteps. And Pierre Leguillon strews 30 pots by the great ceramic artist George E. Ohr (1857-1918) around a Hirst-like vitrine, along with Ohr’s zany promotional photographs. This is not art, it’s art abuse, especially painful since Ohr is as great as Yoakum, whose wall of drawings is adjacent.

The exception is a display of 100 pencil and ink drawings made by North Vietnamese artists during the Vietnam War that the Vietnamese artist Dinh Q. Le is presenting, accompanied by his poignant documentary about some who are still living. They speak for themselves on film, as do the quick, deft ink or pencil renderings of soldiers and civilians on the wall, which fuse Eastern and Western traditions with personal expression, functioning as document, artifact and art.

The 2013 Carnegie International remains on view through March 16 at the Carnegie Museum of Art, 4400 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh; (412) 622-3131, carnegieinternational.org.

Elaine Reichek featured in the New York Times

Art Review

The Jewishness Is in the Details

By KEN JOHNSON

Twenty years ago, the Jewish Museum commissioned Elaine Reichek, the artist known for embroidered and knitted social commentary, to create an installation about being Jewish. What she produced and exhibited in 1994 was “A Postcolonial Kinderhood,” an exceptionally savvy and elegant instance of identity politics in art.

Now, with “A Postcolonial Kinderhood Revisited,” the museum is reprising that exhibition with some minor additions. A pair of bulletin boards display reviews, letters and other materials documenting the original show, and a beguiling short film made from flickering home movies of Ms. Reichek’s in-laws on their honeymoon in 1934 is shown through a porthole in one wall, along with the sound of a piano playing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

But the basic production, which the museum owns, is the same. It resembles a Colonial-era room in a historic-house museum. Framed needlework samplers hang on walls painted grayish green, and a four-poster bed stands in the center on a braided rug. There are also framed groups of snapshots of a well-to-do family, dating from the mid-20th century. You understand that what is actually being evoked is the lifestyle of a modern family whose ancestors might have arrived in the New World on the Mayflower. The antique furniture (in reality, reproductions purchased for the exhibition) has presumably been handed down from one generation to the next ever since. There’s a child-size rocking chair stamped with the Yale University coat of arms, signifying, no doubt, a legacy of Ivy League graduates.

Further inspection peels back another layer. In one corner of the room, there are white hand towels hanging on a drying rack, each embroidered with a monogram made of the letters J, E and W. The samplers, you discover, have stitched into them quotations contributed by Ms. Reichek’s relatives and friends. One advises: “Don’t be loud. Don’t be pushy. Don’t talk with your hands.” More seriously, another reads: “I used to fall asleep every night thinking of places to hide when the SS came. I never thought this was in the least bit strange.”

This is the story of a Jewish family so determined to assimilate into American high society that it almost entirely erases evidence of its own ethnic heritage. Indeed, Ms. Reichek grew up in just such a family and married a man from a similar background. But you don’t have to know the autobiographical details to get the point.

The implicit lesson is that there is a price to pay for hiding certain parts of yourself. What is repressed on the outside may come back to haunt you and your descendants on the inside. Someone brought up in such circumstances might feel a secret, three-pronged shame: shame for pretending to be something you’re not; shame for being something that mainstream society regards as repulsive; and shame for lacking the courage to be publicly what you really are, whatever the prejudices of the dominant culture.

Identity understood from this perspective verges on the sacred. That people should honor their ancestral traditions and not turn their backs on them is an ancient imperative. In the industrialized West of the 1960s, romanticizing ethnic, racial and other sorts of identity was part of the countercultural reaction against the soulless 1950s, when everyone wanted to be like everyone else.

One of the virtues of Ms. Reichek’s installation, however, is that it doesn’t hammer home a message but instead leaves questions hanging. You might wonder, for example, what would a room representing a family that had not suppressed its Jewishness look like? What if Ms. Reichek had grown up in an ultra-Orthodox family?

You might also question a notion of identity that takes ethnicity as essence. Is the truth of who and what you are inseparable from your ancestry? How deep does Jewishness — or blackness or Asian-ness — go?

Historically, there have been good reasons for disguising or rejecting traditional identity. If you live in a society that regards your kind as inferior and unworthy of opportunities afforded its own, it may be pragmatic to unburden yourself of that part of you and pass if you can — a big if for some minorities — as a member of the dominant group.

In a more positive sense, many people have come to this country partly to enjoy the freedom to reinvent themselves. Why not change your name, religion and whatever else in your profile that might impede you in your new home?

These are complexities and contradictions that Ms. Reichek’s installation doesn’t try to resolve, and they give it a resonance that a more didactic work would lack. But those contradictions might be among the reasons that identity art has faded for younger artists, who evidently are suspicious of identifying labels and the limiting expectations that can accompany them. Freely changing identities, putting them on and off like clothes, may be the order of the day, if Miley Cyrus’s appropriation of signifiers from black hip-hop culture is any indicator. The political energy stirring art society today is different and more pointed. Now it’s all about money.

“Elaine Reichek: A Postcolonial Kinderhood Revisited” runs through Oct. 20 at the Jewish Museum, 1109 Fifth Avenue, at 92nd Street; (212) 423-3200, thejewishmuseum.org.

Tony Orrico featured in the Dallas Observer for MAC PAC!

Artist Tony Orrico will bring his movement-based art to the McKinney Avenue Contemporary, first through a 30-hour performance spanning four days beginning September 11 and the next through an intensive two-day performance art workshop called Being to Begin on Saturday, September 28 and Sunday, September 29.

Orrico’s best known for his Penwald Drawings: charcoal artifacts created through performative motion. They’re composed bilaterally, with both hands and both feet acting at once. Like a printing press he moves through or across the surface of a plane, ticking graphite sticks or swishing them around in the palms of his hands – a movement that creates a sound like a stationary rowing machine. He pivots slowly with his wing span doing the work of a massive spirograph, layering lines through repetition.

His project at the MAC, Wane, falls into his new series CARBON. In it Tony abandons symmetry as a starting point and instead rips apart drywall, uses the pressure of his body to set motion to pencils, sews the debris of his deconstructions into new sculptures and finally, gets naked. It’s a life cycle creation where one action’s energy bleeds into the next; art is visible in both the shape of doing and the output of what’s been done.

A project of this scale is a big deal for the MAC. In fact, it represents the first sponsored exhibition coordinated by its young adult member’s program The MAC PAC, which has raised the needed funds for Orrico’s performance. To help bring the weekend workshop to life, a Kickstarter was made. (It’s running now, so go ahead and toss some coin in.)

If you’d like to do a weekend study with Tony Orrico registration opens today. Pop into the MAC and register; the two-day workshop costs $20 for students and $80 for adults and runs from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. each day.

Be sure to view Shirley Tse at the Armory Center for the Arts

The Armory Show and Tell: Shirley Tse presents Quantum Shirley

Quantum Shirley

Quantum Shirley is a framework the artist uses to produce a series of works in diverse media. Quantum Shirley weaves together personal history, New Physics, trade movement and history of colonial products (rubber and vanilla), and the geographical displacement of Chinese nationals in the last century (Chinese Diaspora).

“To escape wars and to seek employment opportunity, my mother’s family was displaced in different parts of the South Pacific and became labor force for plantations. My mother’s immediate family landed in Malaysia and found work in rubber plantations, and her cousin Simone’s family moved further to Tahiti to work in vanilla plantations. My mother and Simone met again in 1968 in Hong Kong when Simone was doing merchandising for her toy import business. My mother moved back to China only to escape it later during Cultural Revolution, when she fled to Hong Kong. Witnessing the financial hardship my mother had to bear, Simone offered to adopt my mother’s four children and me, an infant at that time. Everything was arranged for me to be sent on an airplane in the custody of the airline, but my mother withdrew the arrangement in the last minute and I stayed with her. I often wonder what my life would have been had I grown up in Papeete fostered by Simone. All Simone’s four children were educated in universities in Paris, and some are quite artistically inclined. Perhaps I would have been an artist anyway. Better yet, I believe, in a parallel world, I speak French, have lived in Tahiti, studied at École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, and became an artist. I just simply cannot observe that existence.

“According to quantum theory, if a card falls, it falls on both sides at once. This can be explained by the ‘collapse of the wave function,’ which basically means that thing exists in many states but then collapses into one state when observed. I am intrigued by the ‘validation’ of parallel worlds, paradoxes, and the simultaneity offered by quantum physics. It is interesting that an otherwise tragic personal story can be re-interpreted. When a personal story is seen through other scientific, economic, or historical lenses, a radical change or even a reversal of values could take place.

“I [will] talk about my personal story and map the connections of it to colonial trade, China’s recent history and multiple-worlds theory…[and] show some images and videos I took in my trip to visit Simone in Tahiti, something I have not yet found form of presenting.”

Shirley Tse’s work has been included in numerous museums and exhibitions worldwide, including the Biennale of Sydney; Bienal Ceara America, Brazil; Kaohshiung Museum of Fine Arts, Taiwan; Art Gallery of Ontario; Museum of Modern Art, Bologna, Italy; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; New Museum of Contemporary Art and PS1, both in New York; Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, UK; and Govett- Brewster Art Gallery, New Zealand. Her work has been included in numerous articles, catalogues, and publications including Sculpture Today by Phaidon. She received the City of Los Angeles Individual Artist Fellowship, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship, and the California Community Foundation Fellowship for Visual Artists.

Time:

Saturday, August 24, 2013

12:45 pm - 1:45 pm

Location:

Armory Center for the Arts

145 N. Raymond Ave., Pasadena, CA 91103

Mounir Fatmi interviewed by V&A for the Jameel Prize!

Morocco-born Mounir Fatmi lives and works between Paris and Tangier. He creates videos, installations, drawings, paintings and sculptures that directly address the current events of the world. Here he explains what drives him to create these complex and foreboding works, which he intends to appeal directly to the viewer’s doubts, fears and desires.

Where the Rubber Meets the Road – Jeanne Silverthorne in the International Sculpture Center Blog

In a recent column on Vulture.com, critic Jerry Saltz quoted dealer Gavin Brown about the outsize scale of contemporary art reflecting the outsize scale of the art world: “When we are able to fly around the globe in 24 hours, and that is a common occurrence … these large-scale works might be an unconscious attempt to rediscover awe.” (Never mind that 1960s and 1970s Earth Works were awe-inspiring, supersized, and propagated in the vast landscape of the American West.) Curiously, today there is an antidote to king-size sculpture: an increasing interest in pocket-size work. Parallel to the incredible shrinking sculpture is that these pieces are handwrought by the artist. Embedded in the fast-paced, technology-based, global reach of the early twenty-first century is a simultaneous hankering for intimately created and displayed art. These little works may just be the next big thing.

Thelma, 2005. Rubber, hair and phosphorescent pigment.

4 ½ x 1 ½ x 2 ¼ inches, 11.4 x 3.8 x 5.7 cm. Edition of 10

This is a quiet counter movement by some artists who choose to make diminutive objects rather than massive ones. Matt Hoyt’s (American, b. 1975) small sculptures of hand-held, hand-crafted rocks, chain, bone or twigs were on view in the 2012 Whitney Biennial. Christiane Lohr (German, b. 1965) makes tiny plant sculptures from burrs and thistles. Charles LeDray (American, b. 1960) sews miniature suits of clothing that could fit an elf. And Jeanne Silverthorne (American, b. 1950) is using platinum silicone rubber to create figures that are small in stature but big in attitude. While Silverthorne also makes installation projects of rubber tubing that can span a gallery, her human forms are the size of a coffee cup. When her mini people are poised, seated atop a tall platform, their littleness is exaggerated.

“I really like a range from tiny to large because shifts in scale are like shifts in power,” the artist wrote in a recent email. “If you are looking at something tiny, you are in control of the object, you dominate. But if you are in a room-sized installation or facing a large object, then you are dwarfed by it, disempowered to some extent.”

Thelma, 2005. Rubber, hair and phosphorescent pigment. 4 ½ x 1 ½ x 2 ¼ inches, 11.4 x 3.8 x 5.7 cm. Edition of 10

Their stature reflects a shift in human experience in the world. When enormous work destabilizes the viewer even while enveloping him, the tabletop object offers an opportunity for quieter reflection and even some humor. “I guess there is an aversion to monumentality,” Silverthorne stated. “Somehow the grandiose gesture doesn’t fit with [my] obsession with mortality and extinction.”

Silverthorne’s little people are acutely honed in rubber because the material “was touchable, felt like flesh. It bounced and was funny.” The artist adds pintsize details to each form such as a rumpled sweater, wrinkled flesh, a smear of lipstick or a decorative bracelet. Silverthorne’s figures’ have a yellow bile hue (called “phosphorescent” by the pigment manufacturer, it enables the objects to glow in a darkened room) and she adds human hair to their heads. Through this very current material (Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Richard Serra, Mona Hatoum, Mathew Barney, and Chakaia Booker have all used rubber in their work), Silverthorne is able to reclaim historic sculptural techniques including traditional modeling and casting.

She began working with rubber in the mid-1980s and has continued her fascination with the material. “It literally has no backbone… and therefore it flops around like a slap-stick vaudevillian. Also, rubber effects an ever-so-slight blurring of details, a kind of smoothing out, almost as though there is an echo of fluidity left after the pour has set,” Silverthorne explained.

Intrinsic to her use of rubber to create likenesses of people is the tension that rubber conjures; traits that are dreary, industrial, and dull. But Silverthorne makes objects reeking of vitality: human figures, thriving organic forms and plant matter. “I don’t really see it as lifeless and inanimate…” she said. “Perhaps there is a certain inertness to the material and that would certainly underscore the theme of entropy, of inevitable decay and loss of energy that runs throughout everything I do.”

LA Weekly features Yvonne Venegas

A Mexican Telenovela Spawned a Teen Pop Sensation. Artist Yvonne Venegas Documented the Insanity

By Catherine Wagley

Published June 13, 2013

In a photograph, Anahi, the actress-singer who uses only one name and plays high school superstar Mia in the Mexican telenovela Rebelde, stares at the camera with an expression that looks severe and defiant but probably just reflects the tedium of in-between moments like this one. She’s beside the flawlessly white hospital bed of Miguel (Alfonso Herrera), her father’s onetime enemy, her sweetheart and her bandmate on the show. Because of the coma into which he has mysteriously fallen, literally toppling over midsentence in an earlier scene, he lies with head back and a clear oxygen tube looped under his nose. Shooting has not begun, so cast and crew bustle around the two stars, fidgeting with balloons and cake for Miguel’s birthday party, throughout which he will remain unconscious.

Anahi is incandescent, as usual — something about the way light hits her layered, product-heavy blond hair and made-up skin really does make her glow. Though in this moment, when she looks the part of Mia but isn’t actually playing it, you take her more seriously than you would seeing her on a TV screen, saying something like, “Miguel, baby, I have so many things to tell you” through tears that don’t redden her face.

The photograph, called Cumpleaños (Birthday), belongs to artist Yvonne Venegas’ series Inedito (Unpublished), which features in Venegas’ second solo exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Santa Monica. The series was unpublished for six years, finally appearing last October in a book that Venegas funded via a Kickstarter campaign and published under the RM imprint.

She took the images in 2006, during the last six weeks of filming for Rebelde’s final season, because Mauricio Maillé of the Televisa Foundation’s Visual Arts Department invited her to do so.

The department, backed by Televisa, the Mexican media conglomerate and producer of Rebelde, had just started commissioning contemporary artists at that point, and Maillé had seen an earlier series by Venegas, The Most Beautiful Brides of Baja California, depicting upper-class Tijuana women, many of whom seemed highly conscious of their own carefully composed femininity.

His loose idea was to give the photographer unhindered access to the show’s filming, with a photo book as the possible result.

“He knew there was something there. He wanted me to document the phenomenon,” says the Mexico City–based Venegas, an alumna of UC San Diego’s MFA program and the daughter of a well-known Tijuana wedding photographer.

She makes photographs with the intuitive precision of a good photojournalist, but intends them to be seen on their own, not framed by newspaper headlines or magazine captions.

She doesn’t do much posing or editing, and maybe it’s her photos’ unproduced look that caused the Televisa Foundation to forgo a book — she recently heard certain higher-ups weren’t convinced her images qualified as art — even though that look is a specific strategy. It interrupts the veneer that often surrounds her hyper-produced subjects: the brides; the regal Mrs. María Elvia de Hank, the wife of Tijuana’s wealthy former mayor, whom Venegas shadowed for four years and describes as “a subject with a clear idea of how she wanted to be seen”; or the telenovela stars.

Rebelde, a remake of an Argentine series based on an Israeli show, focuses on a group of students at a boarding school called Elite Way, where, as the name suggests, most come from money and those on scholarship must either prove themselves worthy or be ostracized.

During the show’s 2004-06 run, the six main characters formed a band, called RBD, which became a sensation beyond the show’s frame. EMI Records signed RBD and they toured Europe and the United States, releasing two live albums in addition to their six studio ones.

“This blurring of fiction and reality happened,” says Venegas, who photographed the cast both at Televisa’s Mexico City soundstage and on a U.S. tour, where young fans dressed like Elite Way students sometimes would take photographs of her as she photographed them. Her identical twin sister, Julieta Venegas, had just released 2006 album Limón y Sal, which would sell 50,000 copies in the first two days after its debut, and people understandably mistook the photographer for the musician. So she became part of the identity blurring surrounding RBD.

“I’m interested in the situation, how the photographer becomes part of the situation,” Venegas explains. “They had a dynamic that I could easily play into. There was always a distance, a respectful distance — if I didn’t have a camera, my being there would have been absurd. But there was also a closeness.”

She would go shopping with Christian Chavez, who plays Giovanni and whose hair color changes regularly, or sit with RBD members during downtime.

One image, Dulce en el Telefono, shows a droopy-eyed Dulce Maria, headstrong Roberta on the show, between shoots, wearing her school uniform — a white shirt with top buttons undone and a loose red tie — lying with her head nestled into the corner of a new-looking tan sofa; she has a pillow on her stomach and a black and yellow cellphone up to her ear. Another shows Dulce standing on a balcony poised to drop a book down on suited men while cameras in the foreground record her and a few monitors show a live black-and-white feed of her face and shoulders.

Occasionally, Venegas would photograph the industrial streets behind a Mexico City studio building or a hotel where RBD stayed while on tour, in an attempt to contrast the smoothness inside, which seemed almost ignorant of any other reality, with outside. “The view gives you an idea of class,” she says. “There are so many expectations around the subject. People expect a photographer to see it in a certain way.”

A photographer is expected to criticize when surrounded by the trappings of privilege. But that expectation is limiting and sometimes misguiding. Consider, for example, a 2006 image by photographer Spencer Platt, taken after an Israeli airstrike destroyed a Beirut neighborhood. Well-dressed young people drive through rubble in a gleaming red convertible, one woman taking photographs with her phone. Because of the stark contrast between them and their devastating surroundings, they were misidentified in print and conversation as affluent gawkers. In fact, they were looking for their home like everyone else.

Only a clear caption could have remedied this misread, which is the situation Venegas tries to avoid. Can’t an image invite a nuanced reading without relying on written explanations that detail reality’s complications?