News

Visual Art Source Review - Jeanne Silverthorne

Editorial: Features

Jeanne Silverthorne

Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica, California

Review by Suvan Geer

Continuing through January 3, 2015

Jeanne Silverthorne casts her sculptures in synthetic rubber and with that surprising physicality she earnestly but also playfully autopsies the life out of the contemporary world. “Down the Hole and Into the Grain” is the artist’s continuation of an ongoing examination of nature morte, (dead nature) that plays on the tradition of still life. The translucent softness of the rubber, which Silverthorne has referred to as a kind of “flesh”, makes familiar objects selected from things in her studio and daily life decidedly strange and provocative. Pseudo rolls of wood grained flooring, huge lumber packing crates, blooming flowers, dentures and rolling wood dollies all drop their physical ties to the natural world and become oddly artificial in ways both layered and disturbing.

The artist says in her statement that she is “looking for something that has been lost”. Displayed here in neat aisles like preserved specimens from an underground vault her color-blanched objects offer us the opportunity to ask questions about what is about the natural world that generally goes unmissed in a world of rampant representation and life-like simulation.

What indeed are the signs of life in our brave new world? Living things have an animating force; they move and reproduce. Technology and science have copied and messed with that simple formula until the boundary between naturally alive and life-like is a blur. Silverthorne joins in the fray. In the past she has constructed sculptures that used mechanics to actually move. Some of these sculptures potentially glow in the dark like bioluminescent denizens of the deep, but none of them actively move. Instead Silverthorne parodies procreation. By copying in miniature some organic shaped chunks of rubber left over from the oozing mold making of her sculptures she laughingly treats her fabrication process as female labor and the ongoing copies she makes of the real world as a simulated progeny. It’s a clever shift.

Living things however, also die. Silverthorne’s sprawling coils of cast electrical cable, naked silicone light bulbs, and rubber power boxes give us the industrialized world’s version of life’s animating force reframed as instruments of allegory. With them she brings us to the weirdly absurd activity of considering still life in a world of simulation. Her limp rolls of wood grained rubber flooring signal the process of natural decay by sprouting clumps of equally artificial weeds. Some pristine looking unreal planks crawl like rotting logs with similarly unreal bugs or flies. Her simulated lumber shipping crates sometimes sag towards collapse, but others sit like pale graphic shrines displaying miniature cast self-portraits or posthumous sculptures of people from the artist’s life. In these small figures a pinch of real human hair wildly erupts from each of their colorless little heads. The hair, like growth rings on a tree, is a residue of actual living growth. But here it stands out as the hairline demarcation between life and a manufactured life-like representation. (I have a feeling that visual pun, like others in the exhibit is intended).

All the tromp l’oeil crossovers between real and artificial life and death make for quite a hallucinogenic journey. There are piles of rubber scraps teeming with fake caterpillars, a colorless black and white sunflower committing a slow suicide with a noose made from the cord of a useless electric lamp and elsewhere dead flies pile up beside a stack of ignited gummy dynamite. Yet the tradition of still life images as moral messengers pushes us to read more blatant ecologically related life and death messages into pieces like “Top of the World”. In this sculpture a teacher’s desk globe, totally smooth and eerily white, empty of seas or landmasses, sits beneath a plastic vitrine on top of a fake crate. At the top of the globe two miniature white skeletons are having sex while big black rubber flies either suckle at the globe or lay lifeless beneath it. It’s an emotional and unsettling vision of natural inevitability given an unnatural, toxic connotation by virtue of the artificial materials. A tidy little parable about this reality I don’t want to remember but still find hard to forget.

SWG + PULSE MIAMI 2014

Booth A5 / December 4 - 7 / 4601 Collins Avenue, Miami Beach, FL 33140

Rachel Lachowicz featured in Blouin Artinfo

William Poundstone’s Los Angeles County Museum on Fire

October 6, 2014, 7:29 am

“Variations: Conversations In and Around Abstract Art”

LACMA is debuting a couple dozen newly acquired pieces in “Variations: Conversations In and Around Abstract Art.” Gerhard Richter’s St. Andrew (1988) is the frontispiece, but almost everything else was made in the past few years. (At top is an Aaron Curry next to paintings by Christopher Wool and Mary Weatherford.)

Rachel Lachowicz’s Cell: Interlocking Construction (2010) is an assemblage of plastic polyhedra containing blue powders—cosmetic eye shadows. This experiment in feminist chiaroscuro is shown next to Lachowicz’s Lipstick Urinals, 1992, that LACMA bought in 1995. The pairing makes a concise introduction to Lachowicz. You can say the same for groupings by Sterling Ruby, Mark Grotjahn, and Mark Bradford.

LACMA must have been one of the first museums to acquire a Bradford (in 2003). This year it added two large recent works. Shoot the Coin is one of the best in any museum. Carta (above) has a faux basketball that might recall Joe Goode’s milk bottles.

Speaking of bottles, Amy Sillman’s Untitled/Purple Bottle recapitulates a history of postmodern bottle painting, from Giorgio Morandi to Mike Kelley.

Rashid Johnson’s Afro-futurist psychoanalytic couch, Four for the Talking Cure (left), is from a series shown in London in 2012 “inspired by… an imagined society in which psychotherapy is a freely available drop-in service.”

Think contemporary art is an exclusive club? Dianna Molzan’s Untitled (2012) conjoins a frame with a velvet rope.

A downside of the global art market’s feeding frenzy for contemporary art is that even mid-career artists may be unaffordable by the biggest museums. Going by the quality and quantity of what’s on view, LACMA has moved to the forefront of institutional collectors of art here and now.

Nearly all the work in “Variations” was donated by private collectors, and no single name dominates. LACMA is collecting the old-fashioned way, by persuading wealthy citizens to buy top-of-the-line art and donate it to their city’s museum for the good of all. That’s a “variation” from the L.A. model of even a few years ago. Amen to that.

SWG New Artists Announcement

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is delighted to announce we are now representing

Sabrina Gschwandtner

and

Abdul Mazid

!

SABRINA GSCHWANDTNER

Hearts and Hands Brown and Blue

,

2014

Sabrina received a BA with honors in Art/Semiotics from Brown University (2000) and an MFA from Bard College (2008). She lives and works in New York.

ABDUL MAZID

Occum Nimbus

,

2014

Abdul received a BA in Economics from UC Santa Barbara (2003) and an MFA from Claremont Graduate University (2014). He lives and works in Los Angeles.

Catherine Wagley reviews Yvonne Venegas: San Pedro Garza Garcia

Yvonne Venegas: San Pedro Garza Garcia

Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Santa Monica

Yvonne Venegas, Zally, 2013. Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery

After finishing school, the Mexico City-based photographer Yvonne Venegas worked for a few years for fashion photographers in New York, assisting Juergen Teller and Dana Lixenberg, two photographers known for walking the line between glamour and grit. Without reading too much into those years, it’s worth noting the respect she gives to her subjects’ beauty, and their desire to be beautiful. She frames her subjects in ways that make them immensely pleasing to look at, even when her images have complicated undertones. In the early 2000s, for instance, she photographed the wealthy matriarch Maria Elvia Hank, looking glamorous and composed, placing Christmas candles on a Reindeer-shaped candelabrum. But a servant bends down behind Mrs. Hank, picking up a candle she has dropped, revealing the infrastructure supporting the smooth presentation.

Venegas’s current exhibition, on view through October 25 at Shoshana Wayne Gallery, is called San Pedro Garza Garcia, after the community it depicts. A suburb of Monterrey in the Mexican state of Nuevo Leon, San Pedro Garza Garcia has a population of about 150,000 and the highest per capita income of any Latin American municipality. This attracted Venegas to it, as did the city’s singular ability to ward off the effects of the drug war that has ravaged so many other Mexican communities.

Yvonne Venegas, Rosina and Models, 2013. Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Her photographs don’t allude explicitly to this socioeconomic context. Instead, they portray in between moments in an attractive world that appears relatively self-contained. A group of seven models, all brunette and all in white shirts and jeans, look at fashion magazines underneath a chandelier. Three of them level gazes at the camera. A bride, alone underneath a romantic painting of cupid and a candelabrum, adjusts her dress. Two adolescent girls, lanky and maybe bored, sit on a wrap-around beige couch in a living room that’s impressively clutter-free. It’s pristine but languid: The Truman Show meets The Ice Storm. Even her cityscapes, which suggest the existence of a bigger, rougher world, are suspiciously calm.

Venegas’s subjects are mostly unattainable anomalies but her portrayal of relatable moments behind the scenes blurs the abnormality into normality and makes her work compelling. Her images invite you to try to pick apart the roles people are playing, especially in San Pedro Garcia, where it’s clear class and hierarchy matter, but it’s never clear who has what power in the various moments she’s portrayed.

— By Catherine Wagley 09/29/2014

An Interview with Yvonne Venegas

A Conversation with Photographer Yvonne Venegas

September 16, 2014

Yvonne Venegas | San Pedro Garza Garcia | Shoshana Wayne Gallery | September 6 – October 25, 2014 | http://www.shoshanawayne.com/

I had the opportunity for a Q&A with artist Yvonne Venegas, whose photographs, entitled “San Pedro Garza Garcia,” are currently on exhibit at the Shoshana Wayne Gallery.

How did you first get into photography?

My father is a wedding photographer with a business in Tijuana, and he gave me a camera when I started high school. At first it was just for fun. I found photography to be an easy extension for me as I found in it another way to relate to people, which I enjoyed. At seventeen, I took portraits of my twin sister for the first time. That was, for me, a revelation, as I saw something that, in that moment, I thought I could keep doing for a long time. After that, I began to take photography classes at a community college in San Diego, and that was how my studies in photography began. It was 1988.

How has your work evolved since you first got started?

I kept working with portraiture for many years and studied in various places, including the International Center of photography in New York, which was the first serious photo school I ever attended. I assisted many photographers and soon realized that I wanted to focus only on my personal work. I then did an MFA in Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego, and that experience gave me the tools to continue producing the projects that I have been doing since. My work now is a bit more complex than in the beginning. Now my effort lies in producing complex documents that will hold up in time, and that gives the spectator the possibility to interpret what s/he sees. I am interested in Mexican societies, upper and middle, and making visual interpretations of the various constructions.

Who are the photographers who have influenced you? And the artists?

Over the years, so many! Dana Lixenberg, Rineke Dijsktra, Martin Parr, Tina Barney, Diane Arbus, Ruben Ortiz Torres, Jennifer Pastor, Paul Pfeiffer.

How do you choose your subjects to photograph?

It is an intuitive process, and usually, it has to do with curiosity. I am attracted to subjects that carry a certain level of mystery, and in my work, I try never to reveal it directly — that is, I respect it.

What makes the most successful shoot for you?

It varies. I am still not sure what the formula is, but usually, if I arrive to a shoot not knowing what to expect, I leave with the best feeling. I like to work in a level of the experience. I am living the experience of being with certain people, talking, drinking, and participating, and also photographing. I must feel I know the people I am with in some way in order to produce work that I like.

What makes for the most interesting shoots?

People that are relaxed about how they will be portrayed.

What equipment are you currently using?

A Mamiya 7 with Kodak Portra 400 film.

When you photograph individual subjects, how much time do you use to get to know them?

I go straight to the pictures. If there is time, I stay longer and sometimes keep in touch afterwards for a possible second shoot. Many times, I make friends that I continue to see over the years.

How much planning do you do for each shoot and how much happens naturally?

The planning lies in setting up a meeting time and place. The rest is usually natural. Lately, I have been doing more portraits, which requires a bit more direction. I think there is something great about arriving at a place, like San Pedro Garza Garcia, and simply finding out who is available and willing to be photographed. I also need to plan things when I want to get particular people that I am interested in including in my project, and I think that this is the chapter that I am beginning now in my work.

Can you talk about some technical aspect of your work and photography in general?

When I began to take pictures, I was very much into making beautiful pictures. I studied composition, and I was very good at it. Over the years, I have continued to be interested in beauty, but it is no longer the mainstream view of beauty that I used to enjoy. Now I see beauty in things that can be of balance and imperfect, and this interest has extended onto how I solve images formally. I have been told by photographers that I admire very much that my flash technique is poor. Yet when I hear that word, I wonder, poor according to what standard? I really like how the flash looks, and I have been taking flash pictures for at least fifteen years! So I can say I am not the most spectacular technical person. I have stayed with the same camera and film for a very long time, and I am never the first one to try new gadgets. But formally, I think that my work makes sense with my discourse, both in composition and technique. I tend to print my own work, and that is crucial for me. Overall, I think that to use intuition is more important to me than using the latest of the most perfect technique.

What would you be doing if you were not a photographer?

I think I would be a sociologist or a writer.

Is the process of creating your photographs emotional for you?

Yes. I go through all kinds of feelings, from delight to confusion or from complete confidence to feeling absolutely vulnerable. I think all of these feelings are important as I am trying to create truly authentic documents, and all of those feeling make me think that I am headed in the right direction.

What projects have you planned in future?

I want to try focusing a complete project on masculinity. I am interested in power and fraternity. I have been looking at an all boys school in Mexico called Cumbres that is managed by an order of the Catholic Church called Legionarios de Cristo. Also, I want to start using video as part of the work that I am doing.

What is your present state of mind? What would be next for you if the sky were the limit?

I feel very positive and focused. I am very happy with the work in this show as I feel it brings together a lot of the things that I have been looking at in my past projects, and I think it has the possibility of having many more layers than I have ever tried. I want to publish the book of my past project called “Gestus,” and in a couple of years, the “San Pedro Garza Garcia.” I want to continue producing this kind of work and finding easier ways to finance them as well as to finance my family’s lifestyle. I want to travel to Japan to study bookmaking. If the sky were the limit, I want the work to be in the best collections around the world and to find its place in contemporary art.

KCRW on Rachel Lachowicz at LACMA

Hunter Drohojowska-Philp finds much to admire in new show of contemporary abstract painting

First Clue: Sculpture and video are both featured in this exhibition exploring abstract painting. Why? Because the curators are presenting “Conversations in and around Abstract Painting,” on view through March 22. As in any conversation, varying views come into play and, one may agree or disagree. It is an agreeable way to pass the time in any case, especially since most of the works on view belong to LACMA. Like most museums, LACMA does not have the gallery space to keep everything on view so this is an opportunity to see new aspects of their expanding collection of contemporary art.

A pivotal example is a four-sided bench upholstered in zebra skin with a gathering of plants and a four-sided open black diamond shape in the center by Rashid Johnson, who is about to have a solo show at David Kordansky Gallery. Four for the Talking Cure (2009-2012) was originally made as a place where people could sit and discuss his work. Now owned by LACMA, that is no longer possible but the idea of this exhibition does follow. What do we mean when we talk about abstract art?

The opening salvo from LACMA curators Franklin Sirmans and Nancy Meyer is St. Andrew (1988), a squeeged smear in the colors of blood and chocolate by Gerhard Richter, the German artist who has done so much to complicate the discussions on the meaning of painting. Purchased by LACMA when it was made, it is one of the earliest pieces in the show. In the ‘90s, LACMA purchased a large raw canvas covered in drawn shapes in charcoal, some of which are filled with color, by Laura Owens, another artist who consistently demands more from her painting.

Most of the other works in the show are much more recent, with a hefty percentage being artists from L.A. who now have a significant international presence: Mark Grotjahn, with his paintings of carefully distributed layers of increasingly baroque color as well as two cast bronze masks; Sterling Ruby, with his peculiarly L.A. day-glo landscapes made with spray paint but also his grafitti covered wall operating as pedestal for ceramics; Analia Saban, with her white paintings that document their own process of becoming or unbecoming along with a her white marble Kohler countertop mounted on raw canvas, (a gift from John Baldessari); Mark Bradford, with enormous recent paintings, is concerned with issues of mapping both geographic and historic.

Anthony Pearson brings a refined formalist instinct to his work in non-traditional materials such as subtle shades of gray plaster held in a thin walnut frame; Rachel Lachowicz filled shaped plexiglas containers with variants of blue cosmetic powder — eye shadows! — to construct a powerful wall of geometric abstraction. There is an earlier work, a trio of small urinals made from lipstick. Mary Weatherford’s enticing abstraction melds the flowing paints of color field artists with the mysterious voids of caverns. All this from LA and more: Aaron Curry’s painted sculpture, Diana Thater’s video, it goes on and on.

While there are powerful works by artists who are not living in on the left coast — Theaster Gates, Christopher Wool, Albert Oehlen, Amy Sillman, Howardina Pindell and many others — a conversation about abstract painting is being held in earnest in L.A., which has never been held in high esteem for its traditional painting, abstract or not. It now seems that L.A. artists have re-invented the subject in ways that reflect this area’s ideational as well as pictorial sensibilities. Conceptual abstraction, if you will, is a way for artists to continue to explore the painting of previous generations but to re-interpret it in a way that is newly meaningful. It is an ongoing conversation but this show is a welcome part of it.

The show opens to members today, August 21, and to the public on Sunday. For more information, go to lacma.org.

Join us for an artist talk Saturday, August 23, 2014 at 11:30 AM!

Please RSVP to Alana Parpal : alana@shoshanawayne.com

Thank you to everyone who joined us for the opening of “In-Situ”!

Art in America interviews Izhar Patkin

Interviews Jul. 07, 2014

Rendering the Veil: Izhar Patkin at MASS MoCA

by Phoebe Hoban

Izhar Patkin, Et in Arcadia Ego, 2012. Photo Gregory Cherin.

It took 10 years to develop the unique printer used to create the exquisitely rendered veils at the core of Israeli-born artist Izhar Patkin’s survey “The Wandering Veil,” on view at MASS MoCA (through Sept. 1), in North Adams, Mass. Covering 30 years of the artist’s work, the show includes several key pieces from the early 1980s, when Patkin, who moved to New York in 1977, showed with Holly Solomon Gallery. But at its heart is a collaboration between Patkin and the Muslim poet Agha Shahid Ali, who died in 2001 at age 52.

The central veil metaphor, Patkin explained in a conversation with A.i.A., came about because “we were both interested in veils, which we each had previously used in our work, and we decided that the Jew and the Muslim should meet on a veil. We saw the veil as a physical place of meeting, even though it was ethereal. It was a veil that was meant to reveal, not to hide, and then we took it from there.”

The result is a dreamlike array of ghostly chambers, each with four walls curtained with veils—pleated canvases of tulle netting printed with haunting images. Each chamber contains a bench on which rests a sheet of paper bearing the poem that inspired the images. The show begins with a brightly hued life-size sculpture in anodized aluminum of Don Quixote, reading the eponymous Cervantes novel and holding a mirror that reflects his own image, setting the stage for an exhibit that artfully—and poignantly—explores the relationship between fiction, reality and representation.

Patkin recently spoke with A.i.A. about the show at his Manhattan studio.

PHOEBE HOBAN Can you talk about what themes emerged in putting together the show?

IZHAR PATKIN Principally it was the question of the icon, the question of representation, and options other than representation, such as manifestation. By manifestation I mean a type of visual where, as in pagan religion, the statue is the god. It is not a representation of the god. It is also not an abstraction of the god. I’ve come to understand that representation and the invention of the icon were a deeply Christian phenomenon. Culturally, a very interesting question to ask is how we live under the hegemony of such a canonized idea. So one of my solutions was to turn the image, and its support structure, the canvas, into ghosts.

HOBAN What do you mean by ghosts?

PATKIN A ghost is an unresolved emotion. Once it is resolved it disappears. I think the role of the artist, the writer, is to suspend ghosts, because that suspends the emotion, the drama and the duration. I think the story of the suspended emotion or ghost that appears to take “revenge"—that is the unresolved story—is probably one of the biggest issues of culture today. We are culturally in a time when most of the works that matter are involved in some sort of cultural correction.

HOBAN Can you walk me through the show?

PATKIN The first room is based on a Pakistani poem that Shahid adapted, called You Tell Us What to Do, which is basically a complaint to God. I took that poem and placed it on the beach between Jaffa, the Arab City, and Tel Aviv, the new Jewish city, and I left all the ghosts of that conflict on the beach, as if they were all living still there, all suspended—from famous images of Holocaust survivors arriving to Palestine to today’s Palestinians on the beaches of Gaza. So there are images from different times mixed together, all as if time stood still and nothing ever got resolved.

The next room is based on the poem Violins, which repeats the word until it becomes "violence,” and I had to find a way to visually show that. My solution was to use the idea of the “theater of war,” a very strange concept. So I have the cellist Pablo Casals performing at the White House, where JFK and Jackie sit, and they are facing three other walls which have warlike scenes of armies and death and destruction.

The room called “The Veil Suite” is about Shahid dying. It’s his requiem, in which he becomes God’s bride. On two walls you have a snow scene that could be Kashmir, and then on the other two walls you have train tracks that go from one side of the room to the other, so it’s a good example of how using a room allowed me to create a visual metaphor that could not be done in a conventional painting. And you have the poet rising with the shadow of a photographer taking his picture, and on the other side you have shadows of a Jesus figure and a ballerina doing a pas de deux. The only figure in the entire piece which is actually painted is the picture of the poet.

HOBAN Can you explain the art historical references of the two last rooms?

PATKIN The room called “The Dead Are Here” is my [Jean-Honoré] Fragonard. It’s the unrequited love story of Laila and Majnoon, the legendary Romeo and Juliet of the East. She is reading his letters, which become tombstones, and he is sitting with his dog, because he stopped talking to humans. I took the format of the famous series by Fragonard, “The Progress of Love,” which happens in a glorious Parisian garden, which I exchanged for a cemetery. For the poem called Evening, my [Joseph Mallord William] Turner, I painted Venice, which for me is a place of freezing time, as in the poem, and a magical moment with Turner’s orange sky. So I have a magician sitting on a gondola releasing clouds of dark birds. He is bringing in the night, which will reignite the cycle of light.

HOBAN What about the sculpture toward the end, the porcelain Madonna cast at Sèvres?

PATKIN The Madonna gave birth to the icon. The Madonna is the icon factory—and my Madonna holds a veil, or a canvas, but it’s empty. There’s no baby there. I left it blank because it represents the moment of potentiality. And I also realized that the Madonna, this figure of motherhood, without the baby, is basically a portrait of many of my female friends who don’t have children. So I see it actually as if by strange luck I was given this very contemporary icon—today’s Madonna and child would not have a child. And from the point of view of the painter, the empty canvas is the moment of potentiality.

Artnet news on Michal Rovner

We Love Collecting … Digital Art

Astrid T. Hill, Friday, June 27, 2014

Michal Rovner Most (2011) (ed. 2/3) video/film, framed plasma screen and video.

Photo: Courtesy Ivorypress Gallery

In a recent New York Times article, writer Scott Reyburn asks: “Is digital art the next big thing in the contemporary art world?”

That depends, in part, by what is meant by “digital” art. Of course many artists, Wade Guyton and Christopher Wool among them, have already made a trend of work that is, at some stage, digitally produced. Galleries everywhere are full of paintings, prints, and photos generated digitally and then printed. The distinction here is art that is not only digitally produced but also digitally displayed, very often on-screen. And while the market for such “on-screen” work is still small, the gap between digital production and digital display seems increasingly smaller.

Last October Phillips auction house (in association with Tumblr) held its inaugural “Paddles ON!” sale in New York, consisting of 20 digital works. The auction had a sell-through rate of 80 percent. The highest amount paid for a single work was $16,000, for a chandelier constructed out of CCTV cameras by American artist Addie Wagenknecht, Asymmetric Love Number 2 (2013).

This year’s sale, which began June 21 and continues through July 3, combines an online auction via Paddle8 with a live sale at Phillips. Among the 22 featured works are digital abstracts from Amsterdam-based artist Jonas Lund, photomontages by American artist Sara Ludy, and sight and sound installations from Hannah Perry, perhaps the show’s most purely digital works, displayed on flat-screen video monitors. All of these works are estimated under $17,000 (£10,000) and most are priced far lower at about $3,400 (£2,000).

Jeff Elrod is in many ways a perfect example of an artist born of the digital age, although his techniques to some extent turn the digital paradigm on its head. He began printing computer-generated doodles, made with an old school digital drawing program, while he was a night-shift technician at the Houston Chronicle. Elrod still draws his images digitally, which he then projects onto canvas, then traces with brushes or cans of spray paint. The results are large-scale abstract paintings, which reveal their origins on a computer screen. In March and April of this year, an Elrod show, “Rabbit Ears” sold out at the Luhring Augustine Gallery, and there is currently a waiting list for his digitally-derived abstract canvases. Prices range from $50,000 to $100,000.

Artists like Cory Arcangel see a clear trend from digital production, like Elrod’s, to digital display itself. Arcangel traces the trend back—perhaps not surprisingly—to Andy Warhol and, in particular, to images Warhol made on a Commodore Amiga home computer in the mid-1980s. The images have a familiar, by now nearly traditional iconography, ranging from soup cans to self-portraits to images of Marilyn Monroe.

What intrigues Arcangel, though, is not their familiarity, but the way in which Warhol seems to have anticipated the full digitalization of art. Arcangel argues that Warhol foresaw an increasingly digitized world and that these rediscovered works from one of Pop art’s greatest printmakers already suggest an inevitable movement toward digital display.

We couldn’t agree more, which is one reason we love collecting Michal Rovner’s 2011 video installation Most.

Rovner, who was born in Israel in 1957, works in video, sculpture, drawing, sound, and installation. She has had more than 60 solo exhibitions, including a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art. In many of her works, the installation pieces in particular, history and memory intersect with contemporary politics, science, and archaeology. Most (2011) takes its inspiration from Nobel Prize–winner Wislawa Szymborska’s poem “Microcosmos,” a poem that vividly evokes the fascinations of the microscope, where biology and technology meet under the human gaze. In the video, chromosome-like figures move in pairs, split, and shift, like small creatures playing a game of hopscotch. The work, which suggests the karyotype of some hyper-advanced species, raises questions of identity, inheritance—even the fraught, ongoing history of eugenics, and, above all, the modern collision of evolving life with evolving technology. In this respect, its digitalization lies literally in the tradition of “expressing the material,” giving the piece a powerful sense of inevitability, arising from intellectual and aesthetic coherence.

It is also stunningly beautiful, a nearly archetypal representative of art’s digital future. This is why we love collecting Michal Rovner’s Most.

[Artwork featured is Maja Cule’s The Horizon (2013) HD Video loop, Blu-Ray disc 3'17" which will be offered at Phillips’s upcoming Paddles On! sale in London on July 3 with an estimate of $1,700 to $3,400]

Astrid T. Hill is the president of Monticule Art, which provides art advisory services to private collectors. She specializes in primary and secondary market works of contemporary art.

Artnet reviews Izhar Patkin at MASS MoCA

Izhar Patkin’s Poetic Enchantments at Mass MoCA

Ranbir Sidhu, Tuesday, June 10, 2014

Izhar Patkin, Time Clipping the Wings of Love (2005–11)

Photo: Courtesy the artist.

In Time Clipping the Wings of Love (2009/11), Israeli-American artist Izhar Patkin takes a Sèvres porcelain, originally an erotic setting for a clock, and transforms it through physical deformation and the random application of glaze. It’s a piece that almost disappears in this vast exhibition, “Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil,” a midcareer retrospective on view at Mass MoCA through September 1. On closer inspection, figures emerge, arms, legs, torsos, breasts, women falling somehow. Splotches of dark brown drip along the melted women’s bodies, along with sharp lines of gold.

I passed it by the first time. Fortunately, the artist, a friend, was leading me on a tour. “It’s my favorite piece here,” he said. The glaze, when he applied it, was invisible, and so he had no real idea how it would turn out after firing. Splotches of dark brown dripped down along the mostly melted women’s bodies, along with sharp lines of gold. If he did it again, he laughed, he’d make it even uglier.

This tension, between the ugly and the beautiful, between the mundane and the profound, is on display throughout this sprawling show, which extends over two vast levels of the museum.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

The Messiah’s glAss (2007)

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

The Messiah’s glAss (2007) tackles questions of orthodoxy and messianism in contemporary Israel. The decapitated head of a donkey, cast in glass, is set atop a glass table. A pair of stylized glass testicles hang below the table’s surface, as if its legs were the hind legs of an animal. The piece draws on imagery from the Book of Zohar, where the donkey becomes an image of Satan, and later Jewish theology, in which the so-called “Messiah’s Ass Generation,” lost to God and sunk in debauchery, is believed to usher in, by their extinction, the age of the Messiah.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014).

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

The heart of the show, filling one of the massive main galleries, is the American premiere of Patkin’s longstanding collaboration with Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali. Five rooms have been constructed, each walled with paintings on undulating and often overlapping tulle curtains.

Each room was inspired by a poem by Ali. In one, The Veil Suite, the poet wrote a text specifically for Patkin to work from. Here, the figure of Jesus on the cross dances en pointe with a ballerina on railroad tracks that stretch arrow-straight to the horizon. On the opposite wall, on different railroad tracks, a man stands with his face hidden in a prayer shawl while a photographer crouches under an old-style camera’s hood to take his photograph. The mountains which circle the scene could as easily be in Colorado or the Himalayas.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

The Dead Are Here. Listen to the Survivors

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

In one of Patkin’s most gorgeous rooms, based on the poem by Ali, The Dead Are Here. Listen to the Survivors, a riot of spring colors brings to life a cemetery garden. In the image, a young woman leans her back against a statue’s pedestal while reading a book and a man lies on the grass next to his sleeping dog. White, unmarked tombstones stretch into the distance. The warmth of the day is palpable.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014),

Don Quijote Segunda Parte (1987)

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

Another towering sculpture, Don Quijote Segunda Parte (1987), greets visitors at the exhibition’s entrance, showing the famous knight sitting astride his horse and reading a book of his own adventures while admiring himself in a hand mirror. Taken from an anecdote in Cervantes’s second volume, which humorously acknowledged that in the years since the first book of Don Quixote, others had sought to continue the knight’s tale, it brings to the surface questions of authenticity, the self, narrative, and the curious art of storytelling.

In its circularity, the knight’s vainglorious self-regard, where an imaginary figure reads invented tales about himself, we find a mirror for the tensions that illuminate much of Patkin’s work. Narrative, performance, the self and its creations, are seen in constant and ever-shifting flux. To look for answers here, Patkin suggests, is a fool’s errand, but to ask questions, and to continue asking them, though not a path to redemption, can lead to ever more refined ideas about the possibilities of being.

Ranbir Singh Sidhu is the author of Good Indian Girls and the winner of a Pushcart Prize.

Izhar Patkin, installation view, “The Wandering Veil” (2014).

Photo: Gregory Cherin.

Michal Rovner in the LA Times

Review Michal Rovner charts ghostly migrations

Michal Rovner, “Current Cross,” 2014. Video projection. Audio composed by Heiner Goebbels. (Gene Ogami)

By SHARON MIZOTA

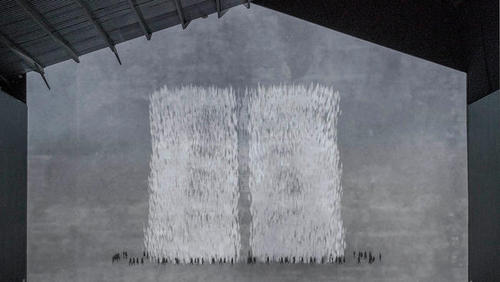

In Michal Rovner’s latest exhibition at Shoshana Wayne, the darkened main gallery becomes a cavernous, hushed space — like a chapel or perhaps a tomb — dominated by the elegant, wall-size video projection “Current Cross.”

It features two large, white rectangles composed of pulsing feathery marks that slowly merge into one and then divide again. Along their bottom edges, a steady stream of tiny black figures makes a ragged procession around the two chalky shapes.

Examined more closely, the shapes are also composed of thousands of little white ambulatory figures. Already elegiac, the rectangles are in fact teeming with ghosts.

This theme is echoed in a smaller projection onto 11 slabs of black limestone. Here, tiny figures crisscross a barren landscape, continually bridging the gaps in the stones, some of which are also covered with the waving silhouettes of cypress trees.

This migratory motif also appears in a group of six ingenious video “paintings,” each spanning two LCD screens butted against each other. Rovner cleverly uses the cypresses to disguise the screen’s hard black frames; the trees simultaneously divide and unite the rocky landscapes.

Rovner was born in Tel Aviv, and it’s hard not to read these images as a kind of Israeli mythology. However, by keeping the figures tiny and nondescript and the landscapes abstract, she has created images resonant of all kinds of displacement. We have all felt like wanderers at some point, trudging we know not where.

Shoshana Wayne, 2525 Michigan Ave. B1, Santa Monica, (310) 453-7535, through July 12. Closed Sundays and Mondays. www.shoshanawayne.com

Copyright © 2014, Los Angeles Times

Michal Rovner featured on KCRW's Art Talk

If you’ve ever stood in front the famous 2,000-year-old Rosetta Stone at the British Museum and fantasized what it would be like to not only read its inscriptions in three different languages, but also to hear these languages spoken and even to see it in the process of being written, then, my friends, I have an adventure for you that will turn all these fantasies into reality.

Michal Rovner, “Current Cross,” 2014

Video Projection

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Internationally recognized Israeli-born artist Michal Rovner is having her third solo show at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Working in such diverse media as photography, painting, sculpture, sound and installation, Rovner is particularly celebrated for her video work.

Michal Rovner, “View,” 2014

LCD screens, paper and video

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Photo Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery

Entering the vast, darkened space of the gallery, one slowly approaches the back wall while staring at its softy glowing black and white video, Current Cross 2014, trying to make sense of its semi-abstract shapes, which brings to mind the iconic compositions of Mark Rothko. To understand and fully enjoy Rovner’s videos, one needs to slow down and stay quiet for a while. That is the way to get them. And by “to get them” I mean not only to see it and to hear its mysterious whispering audio, but also to become aware that what, at first impression, appears to be tiny inscriptions etched into stone, are actually silhouettes of human figures. Hundreds of them. One cannot say whether they are male or female, or what culture and religion they belong to. They are humans. They are us.

Michal Rovner, “Broshei Laila,” 2012

Black limestone and video projection

Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery

In the same main gallery, there is another show-stopping video by Michal Rovner, Broshei Laila, 2012. But this one is projected onto eleven slabs of black limestone. The wide, nighttime landscape is interrupted by dark silhouettes of Cypress trees, looking like exclamation points demanding our attention. And once again, hundreds of tiny white and black silhouettes of human figures are slowly marching through this biblical landscape.

“Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye”

Works from the Gordon W. Bailey Collection

Exhibition at LACMA

In a small adjacent gallery, a few more videos of Rovner’s work are shown on medium-sized LCD screens. In these videos, the artist continues her exploration of landscapes with the Cypress tree and tiny marching figures, but this time she incorporates much bolder colors. Ultimately, it’s up to us, the viewers, while looking at these videos to decide what exactly we are looking at? The pages of the New or Old Testament? Or perhaps at the pages of some other ancient manuscript?

Sam Doyle, “Gulf 7c,” 1982-1985

House paint on wood

Gordon W. Bailey Collection

“Sam Doyle: The Mind’s Eye” exhibition at LACMA

Now, let’s travel back to the 20th century and zero in on a singular figure –– the favorite subject of Sam Doyle (1906 – 1985), an amazingly talented self-taught African American artist from the South. The small but well focused exhibition of his paintings is currently on display at LACMA, where it’s tucked away in a small gallery on the third floor. All works are from the private collection of Gordon Bailey. A few months ago, I talked about some of Doyle’s works at the exhibition, Soul Stirring, at the California African American Museum in Downtown LA. Though painted with house paint, often on discarded metal roofing, his compositions are surprisingly elegant and his choice of color would make even Matisse pay attention. So it shouldn’t be a surprise that among collectors of Sam Doyle’s works are such artists as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Ed Ruscha.

“Ashes and Diamonds,” 1958, Poland

Directed by Andrzej Wajda

Photo Courtesy MoMA

Let me end with a message to all of you, my smart and curious friends. There are a surprising variety of interesting things happening at museums besides their important exhibitions. So you might want to pay attention. Last week, I went to LACMA for the rare screening of Ashes and Diamonds (1958), the seminal movie by Polish director Andrzej Wajda –– astonishing cinematography and heartbreaking story of the last day of World War II.

Space Shuttle Endeavour

California Science Center

Then I attended a fundraiser for artworxLA with its programs to combat LA’s high school drop-out crisis. It took place at the California Science Center, and we were seated under the wings of the suspended Space Shuttle Endeavour. It takes a special occasion to make me speechless and this was one of them. Wow wow wow… And to top it all off, there was a Saturday night concert at the Getty Center by William Tyler, a Nashville-based guitar player, whose acoustic guitars drove the audience wild.

Banner image: (L) Michal Rovner, Shomron, 2012. LCD screens, paper and video. © Michal Rovner, View, 2014. LCD screens, paper and video. ® Michal Rovner. Yaar (Laila), 2014. LCD screens, paper and video. Nofim exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Photo Courtesy Shoshana Wayne Gallery. Other photos by Edward Goldman, unless otherwise indicated.

OPENING TOMORROW:

MICHAL ROVNER

Nofim

May 10-July 12, 2014

Reception May 10, 2014 5pm-7pm

Shoshana Wayne Gallery is pleased to present Nofim, a new exhibition by Michal Rovner. This is the artist’s third solo exhibition with the gallery. Working in video, sculpture, drawing, photography, painting, sound, and installation, Rovner begins with reality and creates situations that illuminate themes of change and the human condition.

With imagery taken from Israel, the landscapes and figures are at once familiar and foreign, calming and disconcerting, personal and political. The figures sway and move yet they do not escape the scene. The scenes are ambiguous enough as to refuse definitive identification yet they are familiar enough as to evoke deep visceral connections.

The power of Rovner’s work rests in her ability to evoke visceral responses to her art. Her landscapes are stripped down, fragmented, and homogenized in such a way that they could be almost any mountainside, desert, or ocean. The human figures are abstracted so as to blur distinctions not only between male and female but also between nationalities –humanity in its most essential form. The cypress trees that are central in this particular body of Rovner’s work, have varied and rich cultural significance worldwide. In the Mediterranean region, it is one of the most ancient trees with scholars noting its presence in biblical writings. In Greek and Roman culture, the cypress symbolizes mourning and hope. For Rovner’s purposes, it is not the cypresses inscribed meanings that are significant, but it is the fact that they exist in the landscape. They are tangible and real marks that either cut or mend a particular scene and the ways they move in Rovner’s work insist upon fluctuation and instability.

In the main gallery, there are two projections. On the East wall Current is projected onto a painted surface. On the West wall Broshei Layla is projected onto eleven slabs of black limestone. While each slab is individually cut, the imagery projected onto them connects each piece while at the same time underscoring their separateness. In this way Rovner subtly shifts the viewer’s attention from implications of archaeology to geopolitical divisions/fragmentations.

In the smaller gallery, there are five of Rovner’s screen works each composed of LCD screens, video, and Japanese paper. These works present barren and ambiguous landscapes, cypress trees and occasionally human figures.

Michal Rovner was born in Tel Aviv, Israel. She lives and works in New York and Israel. Her work has been exhibited extensively worldwide in over 50 solo exhibitions, including exhibitions at prestigious venues such as the Israeli Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, Living Landscape (2005) at Yad Vashem, Jerusalem, the Jeu de Paume, the Louvre, and a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York.In June 2013, Rovner’s Traces of Life: The World of the Children opened at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Among many awards and honors, in 2008 Rovner received an Honorary Doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and in 2010, she was honored with the Chevalier (Knight) Medallion of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France.

For more information, contact Alana Parpal at alana@shoshanawayne.com

Kathy Butterly featured in CFile Online

Exhibition | Kathy Butterly: Little Sexual Beasts at Tibor de Nagy

John Yau, in beginning his review of the deliciously sexy show by Kathy Butterly at Tibor de Nagy (New York February 27 – April 12, 2014), gives a partial list of ceramics exhibitions at major New York galleries over the past 12 months:

“Ken Price: Sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (June 18–September 22, 2013), which I reviewed for Hyperallergic Weekend; Joanne Greenbaum: Sculpture at Kerry Schuss (May 2–June 2, 2013); Betty Woodman: Windows, Carpets and Other Paintings at Salon 94 Freemans (May 7–June 15); Alice Mackler: Sculpture, Painting, Drawing at Kerry Schuss (June 9–July 26, 2013); Arlene Schechet: Slip at Sikkema Jenkins (October 10–November 16, 2013); Mary Frank, Elemental Expressionism: Sculpture 1969–1985 & Recent Work at DC Moore (November 14–December 21, 2013), for which I wrote the catalogue essay; Lynda Benglis at Cheim and Read (January 16–February 15, 2014).

“Current exhibitions include: Jiha Moon: Foreign Love Too at Ryan Lee (February 1–March 15); Norbert Prangenberg: The Last Works at Garth Greenan (February 27–April 5, 2014), for which I also wrote the catalogue essay; and Kathy Butterly: Enter at Tibor de Nagy (February 27–April 19, 2014).”

To this he could have added Edmund de Waal at Gagosian, Robert Arneson at David Zwirner, Gareth Mason at Jason Jacques, Takuro Kuwata at Salon 4 and a few dozen more. Indeed, the 2013-14 art season has been a bumper one for kiln fruit.

It is instructive that Yau offers this list within Butterly’s review because this artist, a student of Robert Arneson, was a trailblazer crossing over into the fine arts with her porcelain vessels soon after graduation and being hailed as one of the City’s most important emerging artists by New York Times critic Roberta Smith.

In a review for her previous exhibition at Tibor de Nagy, Panty Hose and Morandi, Butterly is compared to George E. Ohr (1857-1018) the radical Biloxi potter:

“Kathy Butterly’s current show, Enter, at Tibor de Nagy confirms what I first thought when I reviewed her previous solo show, Panty Hose and Morandi, at the same gallery for the Brooklyn Rail:

“The formal traits she shares with Ohr include a penchant for crumpled shapes, twisted and pinched openings, and making (as Ohr was understandably proud to point out) ‘no two alike.’ Working within the confines of the fired clay vessel, Butterly has transformed this long established, historical convention into something altogether fresh and new, melding innovation to imagination so precisely that it is impossible to separate them.”

This is relevant and obvious. Less apparent and more subversive is her love of Ken Price’s work and the sexual energy one finds in both these artists.

Moreover, Butterly is able to make the miniature monumental. The forms are small, yet labyrinthian; her aesthetic ambition is vast and sprawling. As Yau notes:

“While maintaining a modest scale, she continually reinvents the fired clay vessel (cup or vase) in ways that exceed anything anyone else has done in the medium. From the unique base to the distinct body (creased, collapsing, convoluted and twisted), to the diverse surface, which can run from smooth to craqueled, often in the same piece, to the saturated color (sunshine yellow, fleshy pink, Veronese green and fire engine red), to minute details (yellow lozenges the size of an elf’s pat of butter), everything (including the spills and stains) in a Butterly sculpture attains its own particular identity.”

He continues:

“Butterly’s commemorations of misshapenness contradict a basic assumption in ceramics and, by extension, art, which is it is possible to make a perfect or ideal form, achieve a timeless beauty. The postmodern converse of this ideal, that one can make a perfect corpse (or copy), is well known. Butterly doesn’t buy into these models, with their roots in Plato (the ideal) and Aristotle (classification). Rather, she seems to believe that change is central to experience. In shaping her vessels, she folds, bends and twists the clay, recognizing that anxiety, worry and vulnerability are inherent to existence. Unable to escape time and the constant, multiple pressures it applies, she transforms those forces into contours and forms that are simultaneously goofy and shy, fantastic and disenchanted, gaudy and thwarted, sexy and monstrous.”

The string of pearls, a continuing motif for Butterly, is still with her. One sees this in Scout, almost invisible, minute white beads frame the foot. This fetish jewelry with a thousand sexual connotations is, as I once said when interviewing Butterly in front of a (shocked) Philadelphia audience, is as much a sexual toy as the dildo.

It is liberating to feel her libidinal empowerment as a woman. She is not coy about this. The projection of eros in the art is funky, frank, open, pleasure-seeking and persistent, blending seamlessly with liquid sensuality of her medium.

Garth Clark is the Chief Editor of CFile.

Above image: Kathy Butterly, Dual 2, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 6/8″H x 5 3/8″W 3 6/8″D. Photograph courtesy of the gallery.

Left: Kathy Butterly, Color Hoard-r, 2013, clay, glaze, 5″H x 3 3/4″W x 3″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, Diptych, 2014, clay, glaze, 5 1/8″H x 6 1/4″W x 2 7/8″D

Left: Kathy Butterly, Loud Silence, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 3/4″H x 4 3/4″W x 4″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, Wanderer, 2013, clay, glaze, 6 1/8″H x 6 1/8″W x 6 1/4″D

Left: Kathy Butterly, Jersey Poe, 2013, clay, glaze, 6″H x 5 3/4″W x 5″D

Right: Kathy Butterly, High Life, 2013, clay, glaze, enamel paint, 8 3/8″H x 7 3/4″W x 7″D

Kathy Butterly, Glacier,2013, clay, glaze, 6 7/8″H x 6 3/8″W x 4 1/4″D

Kathy Butterly, Loud Silence, 2013, clay, glaze, 4 3/4″H x 4 3/4″W x 4″D

Kathy Butterly, Scout, 2013, clay, glaze, 3 7/8″H x 5 3/4″W x 3 7/8″D. All photographs courtesy of the gallery.

Artforum - Beverly Semmes talks about her work!

Beverly Semmes

02.05.14

Beverly Semmes, Pink Pot, 2008, paint on magazine page, 7 ½ x 10 6/8".

Beverly Semmes is a New York–based artist who has exhibited internationally since the late 1980s. Her latest shows span the US: Los Angeles’s Shoshana Wayne Gallery is presenting two of Semmes’s large-scale dress works, produced in 1992 and 1994, from January 11 to March 1, 2014. In New York, Semmes will show selections from her ongoing Feminist Responsibility Project, as well as ceramics, at Susan Inglett Gallery from February 6 to March 15, 2014.

IN THE EARLY 2000S, I inherited a stack of 1990s-era porn magazines. It’s a long story in itself, but basically I was helping a friend in upstate New York who wanted to get rid of them but was too embarrassed to take them to the town’s recycling center. I took them home. Not long after, I was working in my studio and I thought: I need these. As I was cracking them open, I had the idea to get some paint out. The first pieces were essentially cover-ups—fluorescent censorships. This is how the Feminist Responsibility Project began. I wanted the FRP works to have a protective aspect: protective to the viewer, protective to the subject. The covering up is nurturing—in a grandmotherish way—and it’s complicated. The redactor is spending a lot of time with the imagery, censoring to keep you from getting/having to see the original material. The images break out of the control: There are rules, but these codes keep getting broken and content slips forward.

I’m often putting this body of work to the side while I focus on another project, but then I end up returning to it. At this point it’s been more than ten years, and I’ve made hundreds. They’ve taken on a painterly surface; they are structured in response to the absurdly concocted magazine scenarios. I make these drawings at the kitchen table. There’s a lot of editing afterward. I’m rethinking and reworking them all the time. There will be pieces in the “not working” category that later become my favorites. It evolves.

I recently installed my show at Shoshana Wayne in Santa Monica—the main gallery is an expansive rectangular space—and the 1994 piece I’m showing there, Buried Treasure, fills the room. Re-seeing this work after many years, I was struck by how much of a drawing it is. There’s one long sleeve and it drapes around the floor. The black crushed velvet is very light-absorbing; it has an oily burnt wood quality, a superblack, like vine charcoal. Many of my sculptures from the ’90s were designed to take up space. The viewer is pushed way to the side; you can’t really walk into the room. Like the FRP, there is a graphic sensibility to my sculptural work of this time. The Feminist Responsibility Project is more intimately aggressive.

As the Susan Inglett Gallery show in New York approaches, I continue to ask myself about the relationship of the drawings to my ceramics. The question has been hanging over my head for at least five of the ten-plus years I’ve been doing the FRP drawings. Ceramics has been my most consistent medium—the one I continue to return to. I began working in clay right after I finished school. The pieces are hand-built. I begin with a lot of very wet clay and then build them up over time, adding handles. They are heavy and off-kilter, and there’s no goal of perfection or lightness as with traditional craft. The glaze has a skin-like aspect; the works are extremely tactile. The ceramics enter into the gallery space as outsiders, as “anti-,” and on some level I’ve always thought of the FRP drawings as doing the same.

— As told to Lauren O’Neill-Butler

Izhar Patkin at Mass MoCA - The Boston Globe

At Mass MoCA, a return from the shadows for Izhar Patkin

By Jeremy D. Goodwin | GLOBE CORRESPONDENT JANUARY 18, 2014

“I’m still alive, alive to learn from your eyes

that I am become your veil and I am all you see”

— Agha Shahid Ali, “The Veiled Suite”

NORTH ADAMS — Sitting over a cup of rice-and-lemon soup in the cafe at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, Izhar Patkin is describing the car accident he’d had a few weeks prior. Headed back to North Adams to finish installing his massive new survey show at the museum after a Thanksgiving respite, the Israeli-born painter and sculptor flipped over his car on the icy Taconic State Parkway, totaling it.

“I thought I was going to die, and I had two thoughts,” he recounts. “I was glad I was alone. Death is personal. It’s nobody else’s business — like going to the bathroom. Then I had the petty thought: They’re going to have to finish writing those wall panels without me.”

For Patkin, musings on eternity mix easily with talk of his show’s details. And his thoughtful, even brooding exterior can lighten quickly for a sarcastic aside or a quick burst of self-consciousness. It fits that his recent work displays an ever-present awareness of death, tinged with darkly cheeky gestures. Patkin appears to have taken his experience in stride, and he has a dramatic new tale to tell.

“Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil,” on view through Sept. 1 at Mass MoCA, caps a return from the shadows for this artist, whose early breakthroughs included a full gallery devoted to his attention-grabbing paintings on black neoprene curtains at the 1987 Whitney Biennial.

This is not only the largest exhibition yet assembled from Patkin’s flamboyantly eclectic mixed media works. (A co-presentation with the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Open Museum in Tefen, Israel, it appeared overseas in bifurcated form in 2012.) It’s also the public’s first extended look at the work Patkin, 58, has quietly created throughout a decade of relative silence.

He’d been a busy art-maker on the rise after moving to the United States in 1977, seeing his work collected by the Whitney, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and other resume-sweetening institutions.

But shortly after the 9/11 attacks, he was stunned by the deaths of several people close to him, all within a year: his father, his best friend and her husband, his longtime art dealer and confidante Holly Solomon, and the Kashmiri-American poet Agha Shahid Ali, with whom he’d struck up a deep friendship and creative collaboration. Patkin quietly dropped out of the art scene, retreating to the sanctuary of his rambling East Village apartment and studio, an urban oasis hewed from a former vocational school.

“It wasn’t a decision,” he says of his inward move. “I just sat in the garden and started taking to the ghosts.”

Now he’s emerging. And he’s been busy.

The centerpiece of the exhibition at Mass MoCA is a suite of new works — five “rooms,” each formed by four hanging sheets of bridal illusion fabric, the stuff of wedding veils. Up to 25 feet long, each is a panel in a wrap-around mural inspired by the poetry of Ali, who was a finalist for the National Book Award in poetry the year of his death. (Ali is buried in Northampton; in his final years, he was director of the MFA program in creative writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, among other academic posts.)

The show also samples generously from Patkin’s earlier work, including startling mixed-media essays that seem to overflow with intertextual references. There’s his colorful blown-glass sculpture of the Hindu goddess Shiva, laced with visual nods to Josephine Baker and Carmen Miranda. (The piece is on loan from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s collection.) There’s a barn wall with a window to nowhere, adorned by a painted scene inspired by both a Franz Kafka story and Pennsylvania Dutch folk art. An oil portrait of a childless Madonna is rendered on wire mesh, its paint casting a shadow on the wall behind.

“There’s an amazing list of materials he uses — anodized aluminum, shadow puppets, video, wax, porcelain,” observes Mass MoCA director Joseph Thompson. “But his subject matter doesn’t move all that much, even though the materials change a lot. I think the nature of fiction and how we represent ideas is really his core interest.”

The new works, collected under the title “Veiled Threats,” are fantasias inspired by Ali’s poetry, as well as by Patkin’s family history and the history of Israel. The artist refers to them as paintings, though he commissioned the invention of a special printer to fashion the images in ink from digital collages.

“It was simply breathtaking, and I think I was mesmerized because I kept on going ’round and ’round and I couldn’t leave the room,” says the late poet’s brother Agha Iqbal Ali, who brought his father and a sister to see Patkin’s take on the poem “The Veiled Suite” in Patkin’s studio shortly after it was finished. He recalls the visit over the phone from a Qatar hotel. “The emotional thing for me is that Shahid died much too young. So when I see this kind of work, I say: What would not have been possible if Shahid had not died?” he remarks, paraphrasing a line of his brother’s poetry.

The veil pieces are crowded with shadowy figures. A magician conjures a flock of pigeons. The crucified Jesus, in a sort of cosmic duet with a ballerina, appears lain across train tracks. “Arik Patkin WTC” includes a photograph of the artist’s father in front of the World Trade Center, taken in August 2001; the bench on which he sits hovers mysteriously.

A sense of the uncanny is heightened by the medium of the veils; the images seem to break apart, or come into better focus, as the viewer moves around the room. The essence always seems suspended between two states. The ghosts are present.

“The dead are very persistent. They don’t leave so easily,” Patkin says, sitting on a stool in his kitchen at home. The shelves there still hold spices that Ali requested Patkin buy, for vindaloo dishes he’d cook as the two got to know each other, exploring a collaboration suggested by a book publisher.

A few feet away lies the courtyard garden where Patkin later made a daily custom of sitting alone, addressing his departed friends and family. At that time he mused deeply on the relationship between reality and illusion, and the notion that unresolved emotions become ghosts — perhaps literally.

“Before I made the veils, I had a deep trepidation,” he says. “I thought, I’m going to make these veils and they’re going to become so material and be so ghostly that once I make them there will be no way back. And I actually thought I will go crazy once they are made.”

He’s been spared that fate; he says the launch of this exhibition instead allowed him finally to let go of this body of work, over which he brooded for so long.

Though “The Wandering Veil” was prefaced by much more modest shows at the Jewish Museum in New York and the Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Los Angeles in 2012-13, it arrives now as an emphatic reintroduction of Patkin to a public that may have lost sight of him for a while.

“I think what would be so important about the show in North Adams is people in the States will see what he’s been up to,” says Nancy Spector, chief curator at the Guggenheim and a longtime friend and advocate of Patkin. “In Israel he’s a kind of national treasure in a sense, but it’s great for people here to know him, and certainly a younger generation that wasn’t going to galleries in the ’80s, didn’t see the [1987] Whitney Biennial, didn’t know what he was doing in the East Village. I think it’s a great occasion.”

Jeremy D. Goodwin can be reached at jeremy@jeremyd goodwin.com.